Three binoculars offering very good performance for a modest price.

April 14 2020

As my regular readers will know, I’ve spent quite a lot of time in recent years seeing what’s what in the binocular market. But just like the telescope market, all is not what it seems. You don’t always get what you pay for and you can find genuine bargains that offer much better bang for buck than those usually presented on internet forums frequented by amateur astronomers, birders and the like. The trouble with these forums is that they usually become hijacked by folk who insist on using and promoting premium products that are usually way beyond the price range of most enthusiasts and many good products simply fall below the radar and so never see the light of day. In this blog, I’ll be presenting three binoculars from the pocket, compact and mid-size aperture range that offer exceptional value for money, having been thoroughly tested(not the usual ‘mickey mouse testing’ seen on the internet) by yours truly in a variety of field conditions.

I’m writing this fully in the knowledge that a lot of folk are hurting financially at the moment, owing to the international crisis precipitated by the corona virus. Millions of people’s mobility has been severely restricted and so there may be quite a few individuals out there who may be looking for cost-effective products that will make life in lock-down that little bit more palatable. What better way than a good binocular to bring the world closer and to examine the beauty of the creation from the vantage of a garden, rooftop or balcony?

All of the binoculars featured in this blog are well made, coupling very good mechanics with excellent optics, all have price tags under £150(UK) and all come with a ten-year guarantee so that if you’re not fully satisfied with the product you can always return it in due course. These instruments include:

The Opticron Aspheric LE 8 x 25 pocket binocular

The Nikon Prostaff 7S 8 x 30

The Barr & Stroud Savannah 8 x 42

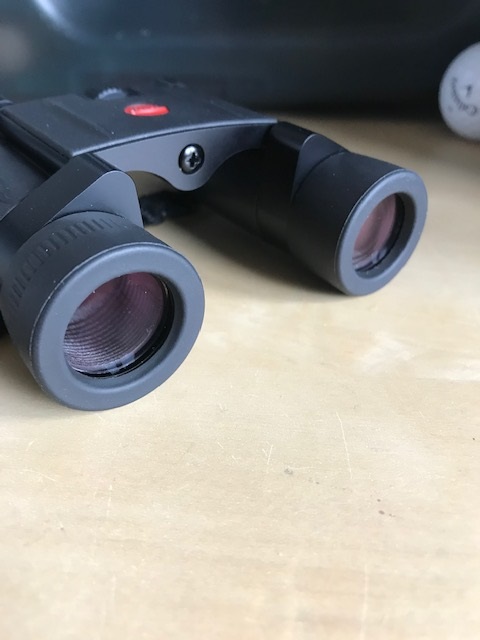

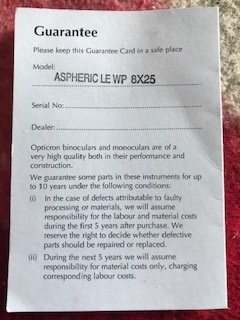

The Opticron Aspheric LE 8 x 25:

The Opticron Aspheric LE 8 x 25 has an rugged aluminium body with dual hinge design that allows it to be folded up into a very small size so that it fits inside a pocket.

Are you looking for a well-made pocket glass that you can take anywhere to deliver very sharp, high-contrast images of your environment? The Opticron Aspheric LE 8 x 25 may be all the binocular you might need. Opticron is a well established British firm with a long history of delivering high quality optical products to their customers. The unit has fully multi-coated optics, high-reflectivity silver coated, phase corrected BAK-4 prisms to maximise light transmission. My glare tests using a very intense artificial light source shows to show up internal reflections and unwanted glare revealed that not one, but two of these instruments produced very satisfactory suppression of stray light. This is a good indicator of high contrast optics even in difficult lighting situations, such as glassing artificial light sources at night and observing heavily back-lit daylight scenes. The unit shown above was purchased for my wife and was acquired before the newer model was brought to market. The only difference between the newer and older models is that the former are fully water- and fog-proof, purged internally with inert, dry nitrogen gas.

The Opticron Aspheric LE folds out to suit most anyone’s inter-pupillary distance( IPD) and has well made twist up eye cups.

Tipping the scales at about 290g, the little Opticron pocket glass has good quality, twist-up eye cups that hold their position well and possess generous, 16mm eye relief, making them well suited both for eye-glass wearers and non-eye glass users alike. The Opticron also features a built-in lanyard for easy transport in the field so there’s no need to fit a strap. Focusing is smooth and precise, and the newer unit has slightly better rubber armouring for comfortable handling in the field. Close focus is also exceptional on these units. I measured one at 1.4 metres!

The Opticron Aspheric LE 8 x 25 allows you to get to work or play quickly.

Optically, these little Opticrons serve up very sharp, high contrast images and their aspherical ocular lenses ensure that the image does not degrade appreciably even when subject is imaged at the edge of the field. The only slight downside with these units is their relatively small field of view; just 92 metres at 1000m(~5.2 angular degrees), but the fine optics more than makes up for this small field!

The newer model comes with a beautiful neoprene carry case that perfectly fits the binoculars.

The well-made logoed carry case fits the pocket binocular exceptionally well for easy transport and storage.

Retailing for £129(UK), these pocket glasses will provide years of hassle-free entertainment that is sure to delight anyone who uses them! I’ve often employed them for limited astronomical applications too, where they have proven their worth in delivering razor sharp and glare free images of the Moon, bright planets, and with an almost flat extended field, are well suited for glassing larger star fields and bright deep sky objects.

An elegant, ultra-portable pocket binocular.

The Nikon Prostaff 7S 8 x 30:

The Nikon Prostaff 7S 8 x 30 compact binocular.

The next binocular featured in this blog was a very pleasant surprise! I took a punt on the Nikon Prostaff 7s 8 x 30 out of sheer curiosity, since the vast majority of comments made by their owners were very positive indeed. And I can now say they weren’t wrong!

Weighing in at 415g, the Prostaff 7s 8 x 30 is very light weight for a binocular with these specifications. The optics are fully broadband multi-coated and the prisms are phase (and silver) coated for bright and sharp images. Being significantly larger than a pocket glass, they are easier to hold and easier to engage with owing to their larger exit pupil( 3.75mm). I was very surprised to learn that the Prostaff 7s has a higher light transmission than Nikon’s more expensive offering, the Monarch 8 x 30, as revealed in my more in-depth review I conducted on this binocular earlier this year. With a length of only 12cm, it is only one centimetre longer than the Opticron pocket glass keeping it very small and tidy!

The Nikon Prostaff 7s 8 x 30 has good quality twist -up and down eye cups that hold their position very well.

Despite being very light weight, it’s very easy to hold steady in my hands owing to its shorter bridge which exposes a larger area to wrap your hands around the barrels. The big focus wheel is buttery smooth and moves effortlessly with zero backlash or slack from close focus (just over 2 metres) to infinity in less than one revolution. The Prostaff 7S has well-made, twist-up eye cups that offers generous (15.4mm) eye relief to suit both eye glass wearers and those that don’t. The poly-carbonate body is overlaid by a thick rubber-like armour with exceptional grip. In addition, the instrument is fully water proof (1m depth for 10 minutes according to the user manual) and being filled with dry nitrogen gas, is also fog proof.

My tests show that the little 8 x 30 was superior to the Opticron in suppressing glare and internal reflections, which came as yet another pleasant surprise to me. Optically, this compact-sized binocular packs a powerful optical wallop. Having a true field of 114m @ 1000m (6.5 angular degrees), the image is very sharp and contrasty, and retains its sharpness almost to the very edge of the field. In addition, there is very little attenuation of light as one moves from the centre to the field stop, unlike many other models I have tested(sometimes costing many times more). This level of optical excellence is achieved by keeping the field of view on the small side compared with many other 8 x 30/32 units you are likely to encounter. I found this a very acceptable compromise though, as 6.5 degrees is still plenty good enough for most applications.

Although the Prostaff 7S units don’t employ ED glass, the chromatic aberration is, to all intents and purposes, non-existent, and delivers no appreciable reduction in performance over an equivalent unit employing ED glass. Like I said before, don’t fall for marketing hype. Most users won’t be able to tell the difference between a unit with ED glass elements and one without, provided that quality optical components are properly assembled in house.

The Prostaff 7s 8 x 30 compact binocular has an exceptionally smooth focus wheel for precision focusing in the field.

Having both larger objective lenses and exit pupils, the Nikon Prostaff 7s is noticeably superior to any pocket glass in low light conditions, where it serves up brighter images at dawn or dusk or on dull winter days. But its biggest performance difference over pocket glasses comes into play when turned on the night sky, where its greater light grasp pulls in significantly fainter stars, making deep sky observing more rewarding.

A fantastic performer for a great price: the Nikon Prostaff 7S 8 x 30.

Together with a good rain guard and high quality padded neck strap featuring the Nikon logo, this 8 x 30 unit is likely to please the vast majority of users and will deliver flawless performance for many years. All in all, the Nikon Prostaff 7s 8 x 30 offers exceptional value for money in today’s market, combining great ergonomics with remarkable optical performance for its modest price tag (~£140 UK).

The Barr & Stroud Savannah 8 x 42:

The Barr & Stroud Savannah 8 x 42 super-wide angle.

Now for a very special binocular. When I started out looking at the modern binocular market, I took the advice of a number of more experienced glassers who recommended I try a Barr & Stroud roof prism binocular. Now, several years on, I’m very glad I did. Every model I have tried for their range has been impressive. But one model in particular stood out from the crowd; the Barr & Stroud Savannah 8 x 42. Having owned and tested two samples of this product, I can say, hand on heart, that it’s got to be one of the best bargains your money can buy.

Built like a proverbial tank, it sports a whopping 143m@1000m true field; one of the widest on the market for a binocular with these specifications. But unlike a string of other models in this modest price class, you get an extraordinarily well corrected field with an enormous sweet spot that keeps the object well focused even near the edge of the field. With a larger exit pupil of 5.4mm, the 8 x 42 is supremely comfortable to use, even by complete novices, since it is very easy to get good eye placement. The body is covered with a thick rubberised armouring, which provides excellent grip even in tricky conditions. Unlike most other roof binos in this price class, the Savannah has its dioptre ring located just ahead of the focus wheel, making it very easy to access should you wish to tweak the optics in the right barrel. On the downside, its location makes it that little bit easier to knock out of place while glassing in the field and so a little bit more care should be afforded to it when removing the instrument from its hard, clam shell case.

Everything about the Barr & Stroud exudes quality. The focuser is a joy to use and one of the best I have experienced in an 8 x 42. It is buttery smooth and moves effortlessly with absolutely no backlash or bumpiness in either direction, taking nearly two full revolutions from its closest focus (under two metres) to beyond infinity. The eye cups are of very high quality and twist up to give extremely comfortable eye relief. What’s more, they remain firmly in place even when significant pressure is applied to them. The instrument is fully waterproof(1.5m for three minutes) and is dry nitrogen purged to eliminate internal fogging when used in cold, damp conditions.

My glare and internal reflections testing showed that the Savannah has exceptional control of stray light and the result is that you get very punchy, high-contrast images. Indeed, the only binocular that has produced better results than the Barr & Stroud Savannah is my little Leica Trinovid BCA 8 x 20, but at a price fully three times the asking price of the former! It has noticeably superior control of diffraction spiking (tested on night light sources) compared with a Zeiss Terra ED 8 x 25 and the aforementioned Nikon Prostaff 8 x 30 and Opticron Aspheric LE.

The Barr & Stroud Savannah 8 x 42(right) has exceptional glare and internal reflection suppression that is only just bettered by the premium Leica Trinovid 8 x 20 costing three times more.

The first model I acquired was second-hand but developed a dioptre fault. But I received a brand new instrument from the parent company who own Barr & Stroud,Optical Vision Limited(OVL) and the rest, as they say, is history. The model features fully broadband multi-coatings on all optical surfaces and phase coated Schmidt-Pechan prisms to boost light transmission and image contrast. It ‘s extremely sharp, even when compared with premium models. In one series of tests I conducted in the summer of 2019, the Barr & Stroud Savannah 8 x 42 yielded images that were only very slightly less sharp compared with an optically perfect Swarovski EL Range 10 x 42. I believe the vast majority of users will be delighted when they look through this instrument. Don’t let zealous binocular gayponauts coerce you into buying a model costing many times more before checking this unit out first!

It might be all the 8 x 42 you need!

The large well-made eyecups and buttery smooth focuser on the Barr & Stroud Savannah make for supremely comfortable viewing.

The 8 x 42 serves as one of the best all-round binoculars for a wide variety of glassing applications, whether it be bird-watching, hunting in low light and for casual stargazing. Its nearly flat, super-wide field will delight those who wish the cruise the Milky Way or ogle large deep sky objects. The only downsides are its weight and slightly lower overall light transmission compared with premium models; at 820g the Savannah is not light by any means but I suppose that, in creating the highly impressive near-flat and super-wide field of view, it needs more optical components to execute this correctly and thus the trade-off is reduced portability and reduced overall light transmission. That said, unlike the two other binoculars discussed in this blog, the Barr & Stroud Savannah 8 x 42 can easily be affixed to a tripod or monopod for ultra-stable viewing, should you require it.

The Barr & Stroud Savannah 8 x 42; a truly remarkable value in today’s market.

This impressive binocular is always a joy to hold in one’s hand and the images it serves up keeps you coming back to it again and again and again. And while you can pick this model up for about £120, I would rank it as my personal favourite binocular. It’s just a supremely sweet instrument made by a company that once supplied optics to the British Navy during two world wars. And that counts for something!

Storing and Transporting the Binoculars

There is further good news when you purchase any of these binoculars. They all come with good quality carry cases. I have already highlighted the nicely designed yellow and black neoprene case fitting the newer Opticron Aspheric LE(illustrated earlier in this blog). The Nikon Prostaff 7s comes with a black padded case with the Nikon logo on the front and fits the binocular very well together with its strap wound tightly around the body. The Barr & Stroud Savannah has arguably the best quality case of the lot though. As you can see form the image below, the 8 x 42 comes with a hard clam shell case that can be zipped up to seal in the binocular and keep out dust and moisture – the destructive enemies of all optical instruments. As with all of my binoculars, I highly recommend placing a sachet of silica gel desiccant inside their cases, as well as leaving the caps for both the objective and eyepiece lenses on for added protection.

All three binoculars featured in this blog come with good quality carry and storage cases. On the left, the original Opticron Aspheric LE had a simpler padded case to the one now being offered. the Nikon Prostaff 7S case is featured in the middle, followed by the hard clam shell case of the Barr & Stroud 8 x 42 Savannah(right).

Well, I hope that you found this short blog useful. Above all, I hope you’ll agree that you don’t have to spend a small fortune to get good optical and mechanical quality. Indeed, those days are well and truly behind us! And if you take reasonable care of your binocular it will provide flawless performance for many years to come.

Thanks for reading!

Neil English is the author of seven books and several hundred magazine articles in amateur and professional astronomy. He has many decades of experience testing and evaluating all manner of astronomical equipment. You can help him continue this work by purchasing one of his books.