A Work Commenced July 24 2024

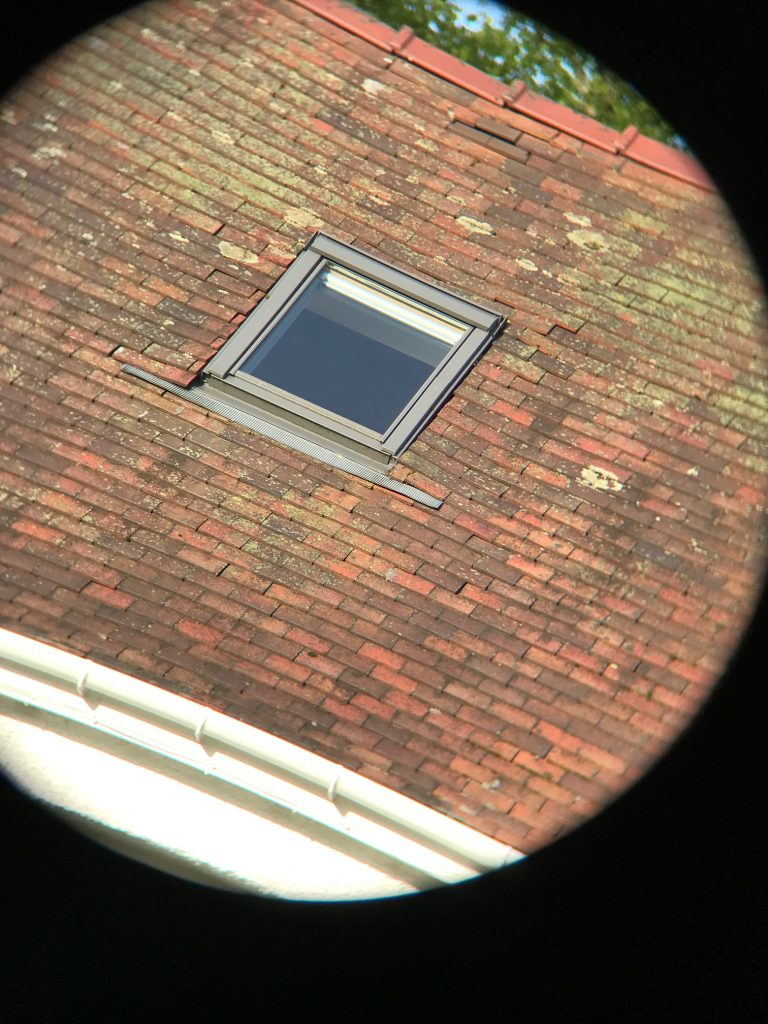

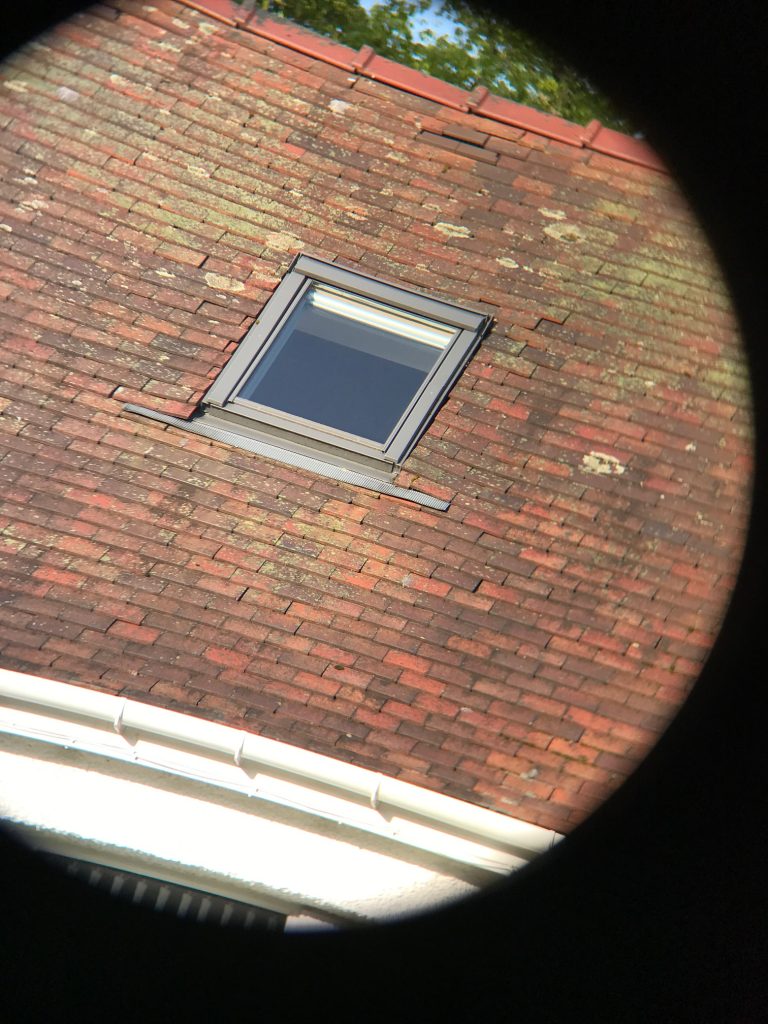

Back in April of this year, I took possession of a new high-performance binocular marketed by Sky Rover: the Banner Cloud(SRBC) 8 x 42 APO. Since then I’ve used and tested it extensively in every conceivable lighting condition, from dawn til dusk and even under the dark skies of northern Italy. These collective experiences have made this author do a great deal of soul searching, to such an extent that I now believe the 8 x 42 to be superior to my beloved Swarovski Habicht 8 x 30W. As a consequence, it’s now become my workhorse birding binocular. The reasons are as follows:

- In good light, it offers the same central sharpness and better off axis sharpness than the Habicht

- It puts much more real estate before your eyes -36 percent more than the Habicht

- It has much better performance against the light – substantially less glare – than the Habicht

- It has significantly closer focus than the Habicht

- Its focus wheel is much easier to rotate accurately and precisely than the Habicht

- Its larger aperture produces brighter, higher contrast images of targets in strongly backlit situations e.g tree branches against a grey sky

- Its larger aperture and exit pupil makes it a much better instrument to use in low light situations or when glassing under a dense forest canopy.

- Its significantly greater mass gives a more stable view with less shake than the lighter Habicht.

I have no doubt the images served up by the 8 x 42 SRBC are absolutely world class. A well known binocular hoarder, and self-proclaimed elitist, possessing all the very best binoculars, described its appeal to a sceptic:

“Yes, the wide field of course, but even more perhaps the very well corrected image across most of that wide field. So far, that was the preserve of the NLs and SFs of this world, so Sky Rover seems to have surprised the market with a „non-premium“ version that imitates the original amazingly well. I am myself truly impressed with the optics of the SRBC.”

Unlike my elitist friend, who probably stores his gear away under glass, I’ve built up a great deal of experience using the instrument in the field, both here in Scotland and abroad in the searing heat of an Italian summer, and so can offer constructive feedback on its robustness and the likelihood of it malfunctioning over time. Well, I’ve immersed these instruments in water with no issues. I tested the functionality of the focus wheel after storing the instrument in a freezer at -20C with no issues. And it coped admirably in temperatures well above 40C(out of the shade). So I have no doubts about its robustness and potential longevity. After all, binoculars are relatively simple instruments with few moving parts. What could potentially go wrong?

Armed with this knowledge and experience, it’s my belief that the hegemony of the European-made binocular has come to an end. I would add that it’s a complete waste of money, in my opinion, to invest in something like a Zeiss Victory SF or Swarovski NL Pure when you have the no frills SRBC giving you the same quality views. The old adage is still true; a fool and his money…..

Birding Experiences with the SRBC

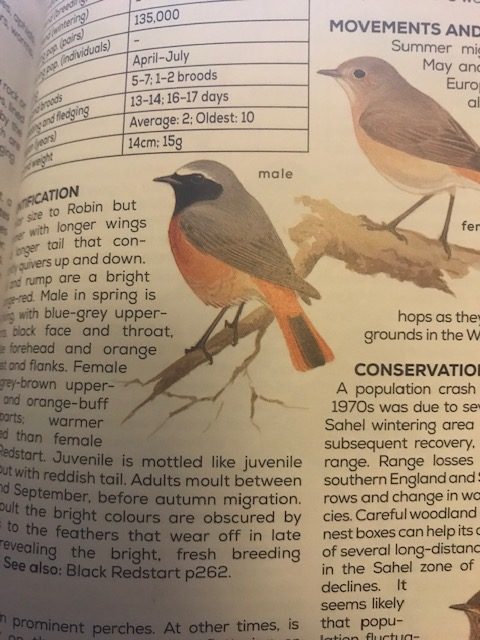

The enormous 9.1 degree field of view allows your eyes to monitor a significantly larger area to spot movements in trees, scrub or open fields. For example, since using the SRBC regularly, my notes show that I’ve glassed substantially more Wrens than I’ve ever done before. These tiny birds are more often heard than seen, but the huge flat field of the SRBC and its amazing sharpness conspire to make seeing their movements within bushes much easier.

It’s superlative sharpness and excellent colour correction makes picking off targets at distance much easier. I have no problems distinguishing airborne Goldfinches from Pied Wagtails for example, at distances up to 150m away.

The SRBC’s excellent glare suppression makes glassing against the light much more productive. Lesser instruments, drowned out by glare, makes it much more difficult to pick off targets when the Sun is close to the horizon.

The silky smooth focus wheel makes following moving targets very easy. Tracking a fast-moving bird flitting from a tree just a few metres away to another location tens of metres away is effortlessly achieved by a gentle twirl of the focuser.

I’ve thoroughly enjoyed glassing open meadows decorated with wild flowers. The huge field, devoid of blackouts is exceptionally immersive: you really get a sense of being in the image. Such carefree glassing has proven very profitable for birding too. For example, just the other day, I was doing just this with the 8 x 42 SRBC, strolling along a country road when a female pheasant together with her clutch of youngsters emerged from the long grass just a few yards from me. The SRBC revealed extraordinarily fine details of its plumage and long, elegant tail. Astonishing!

I’ve also enjoyed glassing long into the evening twilight, watching badgers treading their paths across nearby fields, stopping every now and then to sniff the dew-drenched grass, and using their powerful front paws to dig for roots. Pipistrel bats emerging from Culcreuch Castle often descend on the nearby pond to feast on insects and its been thrilling to watch them with both the 8 x 42 and its larger 10 x 50 sibling.

I’ve ordered up a custom iPhone adapter to do some imaging, as well as some extra eye cups to store as backups if need be. I’m also considering a bino harness to support the weight of these instruments for longer duration glassing events. I’ll let you know how I get on with these in a future blog.

All in all, I’m thrilled to bits with these new optical wonders from Sky Rover and heartily recommend them to other members of the birding community.

Notes from the Field

Upon my return from Italy, the instrument was found to have a significant amount of dust. It was everywhere: on the rubber armouring, on and around the objectives and eyepieces. When I unscrewed the eyecups from the instrument, I found a layer of fine dust there too. The instrument was throughly cleaned.

I store my SRBC binoculars in sealed Tupperware containers with large quantities of desiccant even though they are water proof and gas filled. That way they are ready to use at a moment’s notice. My ongoing experiments show that regardless of how well sealed a binocular is, it’s only a matter of time before the dry nitrogen will outgas. These containers draw all the water from the inside of the barrels and so will remain fog proof. And provided they are returned to these small containers when not in use, there is no need to have them refilled with nitrogen.

While the 30-32mm aperture class is good for many purposes it is not optimal. Even on bright days, there will be many scenarios where the greater contrast garnered by the larger 42mm aperture will prove superior to the smaller class. In particular, I’ve noticed the superior performance of the 42mm glass glassing trees against a bright overcast sky. In addition, the larger eye box makes for a more comfortable viewing experience.

Thanks for reading!

Post Scriptum: August 1 2024

I recently bought in a Leica Ultravid HD 8 x 42 to compare it with my SRBC 8 x 42. The Leica is lauded for its crystal clear views and excellent resistance to glare. Here’s the breakdown based on a couple of days of daylight testing.

Ergonomics: while the Leica is shorter and more compact, it’s still quite hefty at about 790g( the SRBC is 863g without ocular and objective caps). In my medium sized hands, the Leica was harder to get my fingers around the barrels. The SRBC was much more comfortable for me with its shorter bridge. The focuser was a real disappointment on the Leica. It was not silky smooth like on the SRBC, with quite a bit of uneven resistance. It also had some significant free play which really niggled me. The eyecups were judged to be equally nice on both instruments.

Hydrophobic coating test: the SRBC coating proved the equal of the Leica( Aqua Dura) in being able to disperse a thick layer of condensation applied to the 42mm objectives. Both instruments dispersed this condensation with equal speed.

Optics: The Leica Ultravid has very fine optics to be sure but I judged the SRBC to be superior overall.

Shining an intensely bright beam of white light from across my living room showed up excellent results with both instruments. I would give the SRBC the nod though in having slightly less internal reflections (read very minimal).

Glassing rocks and the grain on the trunks of trees in the middle distance showed their sharpness to be identical in the centre. The Ultravid HD might have had slightly more ‘sparkle’ and slightly more saturated colours but the differences were very subtle to say the least. Glare suppression was very good in the Leica but it was inferior to the SRBC, as evidenced by glassing some shaded vegetation immediately below a bright afternoon Sun.

Off axis aberrations were better controlled in the SRBC too, especially pincushion distortion, which was much more pronounced in the Ultravid HD. Chromatic aberration was excellently controlled in the centre field of both instruments, but was a little bit more pronounced in the Ultravid HD near the field stops. Close focus was a tad closer in the SRBC than in the Leica.

With a field of view of just 7.4 degrees the Leica Ultravid HD has a portal fully 50 per cent smaller than the SRBC and it really shows! The SRBC view is just far more compelling IMO. Image brightness appeared the same after sunset. The Leica has a measured transmission of 90 per cent for reference.

In summary, I have no doubt that the SRBC is a more technologically advanced binocular than the Leica Ultravid HD. Kudos to the PRC!

Update August 6

Testing Against a Zeiss Conquest HD 8 x 32

Some background: the Zeiss Conquest HD series is widely regarded as upper mid-level in terms of optical performance and in general rates among the best of the $1K priced binoculars on the market as of very recently.

The following observations were made only during bright daylight, either in bright sunshine or bright overcast skies. But I also tested for artefacts by shining a bright white light beam through the instruments.

Bright light test: The Zeiss Conquest HD(CHD) showed excellent control of internal reflections but did display a very prominent diffraction spike. The SRBC also showed no internal reflections and no diffraction spike. The same result occurred when I turned it on a bright sodium street lamp after dark about 100m in the distance. The spike was annoying to see in the Zeiss CHD. Not an instrument I’d choose for glassing harbours or cityscapes at night.

Colour tone: Comparing both instruments, I was immediately struck by the cooler colour tone of the Zeiss. This is well documented in the literature. Glassing flower baskets and beds showed the SRBC to have richer, more vibrant colours.

Sharpness: Central sharpness was a tad better in the SRBC and maintained better sharpness as the target was moved off axis. I would say the SRBC image displays significantly more ‘bite’ than the Zeiss CHD.

Image Immersion: The wider flatter field of the SRBC produced a much more immersive experience,as if one were sitting in the image. That said, for a 8 x 32, the 8 degree Zeiss is very nice!

Off Axis Aberrations: These were well controlled in both instruments. The SRBC had a tad less pincushion distortion and significantly better edge-of-field sharpness compared with the Zeiss CHD.

Chromatic Aberration( CA):

Glassing through several layers of defoliated branches on a dead tree against a bright overcast sky showed very little longitudinal CA in the centre of the image, with the SRBC being a little better in this regard. It was a totally different matter with off axis(lateral) CA though. The Zeiss CHD showed significantly more, both in extent and intensity.

Glare: Both instruments display well above average suppression of glare against the light, but the clear winner, once again, was the SRBC.

Focusing: the Zeiss CHD has a very fast and silky smooth focus wheel displaying no free play or uneven resistance to movement throughout its travel both clockwise and anticlockwise. But it’s so fast that one can often overshoot on the target and so requires a little bit more concentration to get it just right. In contrast the SRBC focus wheel is more refined in my opinion. it’s smooth but has more traction allowing one to get the focus right first time, every time.

Close focus: the Zeiss CHD has a shorter minimum close focus(well under 2m) compared with the SRBC.

In summary; the Zeiss Conquest HD is a good step down from the SRBC 8 x 42. Nearly everything about it is underwhelming in comparison. If weight is not an issue the SRBC is clearly the better choice for birding and general daylight glassing etc.

Update August 14

Zeiss SFL 8 x 30 versus SRBC 8 x 42

Introduced in 2022, the SFL series retail for £1300 to £1600 here in the UK.

Summary: Much closer than I expected but still no cigar.

The Zeiss SFL is a real class act with some of the best images I have experienced in a compact class binocular, but it exhibits higher levels of colour fringing in its outer field compared with the SRBC, as well as noticeable field curvature which softens its edge performance.

Details:

White light test: the Zeiss SFL has higher quality prisms than the Conquest HD, as evidenced by the absence of a diffraction spike. It proved as good as the SRBC in this regard, with very subdued internal reflections.

Glare suppression: is a step-up from the Zeiss CHD, and is as good (if not a tad better) than the SRBC against the light.

Colour tone: These looked almost identical to my eye under a variety of different lighting conditions. The SFL showed the same vibrant but accurate colours of flowers and shrubs as the SRBC and distinctly different from the cooler tones seen in the Conquest HD. A very pleasant surprise!

Central Sharpness: As good as the SRBC in good light i.razor sharp, excellent.

Off-Axis Sharpness: the SFL loses critical sharpness gradually as it’s moved off axis. The outer 20 per cent of its field is noticeably softer than the SRBC which I suspected was due to field curvature. Star testing confirmed this. Centring pinpoint sharp Vega in the field of view of both binoculars and panning off centre showed a pronounced bloating of the star which was very obvious in the outer 20 per cent of the field of the SFL Much of this could be focused out however, indicating that field curvature was indeed the major contributor. In contrast, the SRBC showed very little or no departure from pin sharp all the way to the field stops.

Chromatic aberration:

The UHD optical system in the Zeiss SFL provides crisper images with higher contrast than the Conquest HD. That said, it was no match for the SRBC in terms of colour correction. While both instruments showed essentially none in the centre, moving off axis in the SFL showed significantly higher levels of lateral colour than the SRBC, which in contrast showed very little. I feel the SFL is a high quality ED binocular but can’t match the true APO billing of the SRBC.

Focus Wheel: The SFL has a super nice and responsive wheel with near perfect amount of traction. More refined than on the Conquest HD. And just like my SRBC, it shows a little bit of resistance at the end of its anticlockwise travel.

The Overall View: Both are very relaxing to pan, showing very little or no rolling ball effect, and no annoying kidney beaning. Eye relief is a little better in the SFL. The significantly wider (8 vs 9.1 degrees) and flatter field of the SRBC creates a more immersive and majestic view that is just so addicting.

Conclusions: Superior colour correction(owing to the use of Ultra FL), ultra flat, and ultra wide field are hallmarks of Zeiss’ flagship models: the Victory SFs. The SRBC should rightly be compared to the SF or indeed the Swarovski flagship line, the NL Pure, which may close or exceed the performance gap.

Update August 24

CNer Koh from South Korea did a shoot out between a 10 x 42 SRBC and a Leica Noctivid 10 x 42, declaring the SRBC the easy winner. Later in the same thread he compares the 12 x 50 SRBC with the Swarovski EL 12 x 50 and found the former to be superior over all. Details here.

Just for the fun of it, I cross posted Koh’s review over on the bino porn site on Birdforum. Ruffled a brood of vipers and flushed out the haters. The reader will note it’s the same folk who have never looked through the SRBC that are most critical of it. Yip, the classic argument from pure ignorance.

Infamy!, Infamy! ….. they all have it in for me! Lol

Job done.

Maybe now I should take up collecting watches or something?

If you like my work please consider buying a copy of my new book: Choosing & Using Binoculars, packed full of hot bargains that won’t break the bank.