A Work first Published in Touchstone Magazine March/April 2022

Return of the God Hypothesis: Three Scientific Discoveries That Reveal the Mind Behind the Universe

by Stephen C. Meyer

HarperOne, 2021

(576 pages, $29.99, hardcover)

Return of the God Hypothesis is the latest work from the distinguished philosopher of science, Dr. Stephen C. Meyer, Director of the Center for Science and Culture at the Discovery Institute in Seattle, Washington, and one of the world’s leading proponents of intelligent design (ID). In it, Dr. Meyer shows that science at its most cutting edge has thoroughly vindicated those who have clung to a deeply held belief in a personal God who operates beyond space and time. From the earliest moments of the Big Bang, to the formation of the first living cells on earth, and on up to the present day, the extraordinary fine-tuning we observe in all realms of nature shows us that God has truly left his signature on the very large and the very small.

The thesis of this book is that modern scientific discoveries testify to the idea that a mind vastly superior to our own not only created the universe, but also purposefully arranged for it to have precisely the properties required for human life to exist and flourish. Meyer examines three seminal scientific discoveries to support his thesis: (1) that organisms contain biological information whose source cannot be merely physical or material; (2) that the laws of physics have been finely tuned to sustain life in general and human life in particular; and (3) that the universe had a specific beginning in space and time.

Building on his previous best-selling works, Signature in the Cell and Darwin’s Doubt, which examined the implications of biological information, Meyer now brings cosmic fine tuning and the origination of the universe in a Hot Big Bang singularity into the discussion to argue persuasively that the single best explanation for all three phenomena is a personal God who transcends the spacetime continuum and has intervened throughout cosmic history to ensure that creatures shaped in his image would one day appear on earth.

Theistic Cosmology: The Big Bang

These three ideas were not birthed in a vacuum. The scientific revolution, Meyer asserts, began in Reformation Europe and was firmly moored in theistic principles. Quite simply, to study the universe was to get to know the mind of God. That’s why so many of the founding fathers of science—Robert Boyle, Isaac Newton, Johannes Kepler, and René Descartes, to name but a few—framed their scientific knowledge in terms of “understanding God’s thoughts after him.” They all saw within the pages of Scripture a God who set boundaries for the tides and the winds and ordained the orderly motion of the moon, stars, and planets, a law-giving God who limits human life span to curtail the spread of personal evil within any individual.

But as the Renaissance gave way to the Age of Enlightenment, scientists abandoned these theistic principles and sought instead to formulate a purely materialistic narrative of cosmogenesis. The great celestial mechanician, Pierre-Simon Laplace, declared in the eighteenth century that there was no need to invoke a deity to explain the complex motions of the celestial bodies, and Charles Darwin posited in the nineteenth that humans evolved from lower animals through a mindless process he called evolution. The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries saw scientific materialism reach its zenith and even spill over into political and psychological discourse in the works of such atheists as Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud.

Yet with the inexorable march of science into the twentieth century, theism came back with a vengeance, starting with Edwin P. Hubble’s discovery that the universe was constantly expanding. This was followed by Georges Lemaitre’s discovery of evidence for a sigular cosmic event which brought the physical world—space, time, matter, and energy—into existence all at once at a particular point in the finite past. Lemaitre’s theory—for he was both a Catholic priest and a prominent physicist—came to be known as the Big Bang theory.

Meyer relates how many of the great astronomical minds of the era found such origin stories “philosophically repugnant” and went to great lengths to repudiate them. In fact, the distinguished British astrophysicist Sir Fred Hoyle coined the phrase “Big Bang” as a term of derision. He countered the idea of the universe having a definite beginning with his own “steady state” theory of a universe that was infinitely old. This was the conservative view among scientific materialists at the time.

But as militant as Hoyle became in advancing his steady-state cosmology, the evidence for the Big Bang grew ever stronger as the twentieth century wore on. And some distinguished scientists, such as the Mount Wilson astronomer Allan Sandage, began to see the unavoidably theistic implications of a universe that had a beginning. Ultimately, the evidence for the Big Bang theory led Sandage to faith in Christ at the end of his life.

Theistic Biochemistry: Genetic Information

In exploring the current state of origin-of-life research, Meyer shows that despite the best attempts of materialist scientists to re-create the first chemical steps toward life, they have been unable to do so, but in the process have inadvertently shown that an inordinate amount of intelligent design—far in excess of current human capability—is required to bring a living organism into existence. Indeed, by calling on experts in organic chemistry, Meyer shows that even the first steps toward creating a biomolecular assemblage require many intervening stages that cannot be achieved naturalistically. He writes:

The discovery of the functional digital information in DNA and RNA molecules in even the simplest living cells provides strong grounds for inferring that intelligence played a role in the origin of the information necessary to produce the first living organism.

The thorny question of life’s origin leads Meyer to explore an even more fundamental problem for scientists who hold to a strictly materialistic narrative of how we got here. He doesn’t shy away from asking where the stupendous amounts of new genetic information came from that are needed to build complex cells and new body plans. He shows that even the most hard-nosed evolutionary biologists duck that question time and time again because no rational answer is in sight.

Theistic Physics: Fine Tuning

Moreover, it turns out that we live in precisely the kind of universe that can allow living things to exist in the first place, not to mention allowing human life to flourish. Specifically, if the strengths of the various forces of nature or the properties of the particles comprising the material universe were only very slightly different, we simply wouldn’t exist at all. This is known as the fine-tuning problem. Meyer reminds us that some of the best minds in the industry have been thinking deeply about it.

The distinguished theoretical physicist Sir John Polkinghorne believes that cosmic fine-tuning provides very powerful evidence of design. Brian Josephson, another British Nobel Prize-winning physicist, has stated frankly that he is 80 percent confident that some kind of intelligent agency was involved in the creation of life. The same evidence caused the outspoken philosopher Antony Flew to reject his own long-time atheistic teachings, which he had clung to for most of his life, in favor of deism. As Christian astronomer Luke Barnes writes: “Fine tuning suggests that, at the deepest level that physics has reached, the universe is well put together. . . . The whole system seems well thought out, something that someone planned and created.”

Nevertheless, some materialist physicists have invoked an entirely speculative concept to explain away the creation of our fine-tuned universe: namely, the weird and wonderful “multiverse,” or as some refer to it, the “many worlds hypothesis.” Our universe appears the way it is, these advocates claim, because it is just one among an infinite number of universes whose physical laws and material properties are all different. Logic dictates that a small number of these universes must contain conditions that are ripe for the development of life and human intelligence, and ours just happens to be one of them. No creator God needed.

Meyer calls upon some towering figures in the philosophy of physics to demolish the multiverse hypothesis. Roger Gordon, for instance, has compared the attempt to promote the multiverse theory to “trying to dig the Grand Canyon to fill in a pothole.” Other intellectuals have delivered their own verdicts on the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics. Richard Swinburne of Oxford University likes to invoke Occam’s Razor in deciding whether a theistic or multiverse worldview is more likely. Since theistic beliefs require only one explanatory entity, he argues, over the multitude of entities required for the multiverse, the theistic model is more rational and more likely to be true.

Cosmic Gerrymandering

Desperate attempts have also been made by influential cosmologists to avoid the obvious theistic implications of a universe that had a definite beginning. In particular, Meyer uses his considerable skills in philosophy to debunk the lofty-sounding proclamations of celebrity cosmologists such as Lawrence Krauss, the late Stephen Hawking, and others, who have sold millions of books with headline-grabbing titles like A Universe from Nothing and The Grand Design.

Meyer also examines the technical details of the real physics underlying their claims. For example, he notes that Hawking ducks the issue of a beginning by introducing “imaginary time” into the equations of general relativity. While these modifications do seem to avoid a singularity, his critics have pointed out that they are merely mathematical constructs that do not comport with physical reality. Hawking also introduces ad hoc treatments that appear simply to have been motivated by his philosophic disliking of a first cause.

Meyer lays out similar devastating arguments against other theorists who have waded in on this issue, especially Lawrence Krauss and Max Tegmark. Above all, Meyer shows that while these men may be brilliant scientists, they turn out to be very poor philosophers.

If God, Which God?

If, as Meyer asserts, the God hypothesis is the single best explanation for why the universe is the way it is, can we then infer anything about the nature of that deity? Meyer discusses the three main possibilities: pantheism, deism, and theism.

Pantheism asserts that God is the totality of all of nature, the Brahman of the Eastern religions. Meyer shows that pantheism cannot account for the cosmic fine-tuning we observe, because the deity that created the universe must necessarily transcend space and time. All the great religious texts of the Orient, however, describe a deity who must have begun to exist only after the universe came into existence.

Deism, on the other hand, posits a transcendent God, but it denies any involvement of that God in the workings of nature after the beginning. In other words, God somehow front-loaded the laws of nature so as to guarantee that creatures like us would some day emerge, but he then stepped back and let things proceed on their own.

The actual scientific evidence we have, however, indicates that God has played an active role in his creation throughout time. For example, vast amounts of new information had to have been introduced when the first complex animal body plans appeared during the Cambrian Explosion, some half-billion years ago. The fossil record shows clear evidence of mass extinctions followed rapidly by the appearance of entirely novel forms of life. That comports with a God who is always working, as the Lord Jesus said: “My Father is always at his work to this very day, and I, too, am working” (John 5:17).

Although Meyer concentrates on just three issues in this book—fine tuning, the origin of biological information, and the singularity at the beginning of time—there are other natural phenomena that also point towards a creator God. The hard problem of consciousness, for example, is still a profound mystery, especially for those who hold to a materialistic or evolutionary world view, yet it fits neatly into a theistic framework.

Can scientific research go a step further and trace a path from theism to Jesus Christ? While Meyer is a Christian, he does not address that question in this book, at least not directly. Perhaps that discussion will become part of Meyer’s next literary project? If so, it will certainly be worth reading, too!

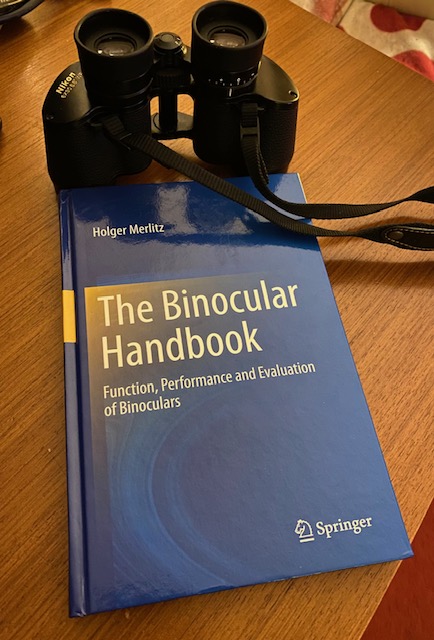

Dr. Neil English is busy writing his latest book, Choosing Binoculars: A Guide for Stargazers, Birders and Outdoor Enthusiasts, which will hit the bookshelves in late 2023.

De Fideli.