In this new blog I’ll be sharing my experiences as an astronomer who took up birding only a few years ago, as well as offering advice to beginners.

Tune in soon for details……..

ISBN: 978-3031447099

523 Pages

Foreword by Holger Merlitz, author of The Binocular Handbook

Price: £20.84(UK)/$32.99(US)

Available Now

Dear Reader,

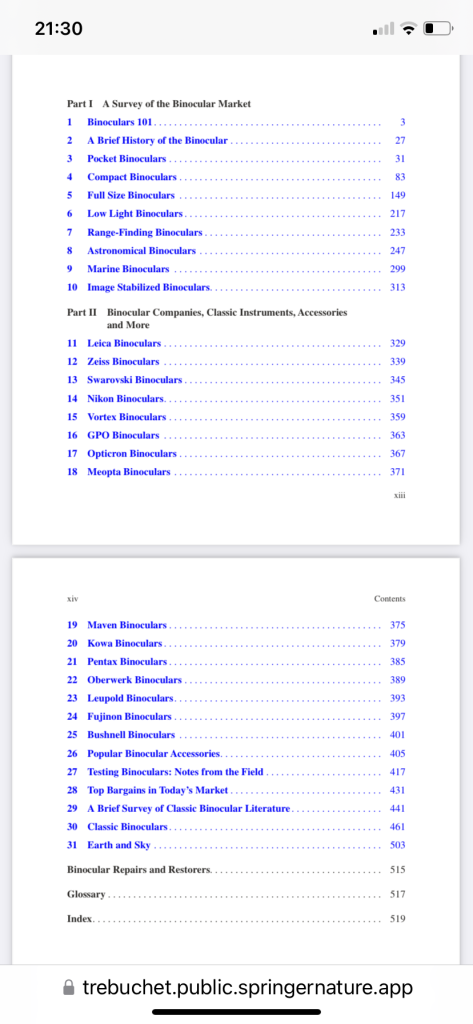

My new book on binoculars is ready for purchase from Amazon and all good booksellers. Below is a list of the chapters presented in the book.

I hope that you will support me in my work.

Sincerely,

Neil English

Regarding the Obserwerk SE 8 x 32 ED

SN: 232161

Sunday September 10 2023

Dear Mr. Busarow,

After reviewing and continuing to use the 8 x 32 SE for a further seven months, I am more impressed than ever with this instrument. I’m not at all surprised that it has garnered more than 10,000 views on Birdforum alone, and an even greater number of visits on my website. As detailed in my original review, I showcased many terrific features of this instrument which I will summarise as follows:

I’ve already commented that its sharpness and colour correction are superior to the highly rated Nikon E II 8 x 30, but its optical and ergonomic excellence has also been noted by a number of other experienced observers including the Irish birder, ‘Sancho,’ who compared it to his Zeiss TFL 8 x 32 and, based on subsequent field testing, now uses it as his ‘favourite all-round’ birding instrument. I would like to remind you of his posts here:

My Oberwerk SE 8×32 arrived today. I haven’t had much chance to “test” it, and in any case a birding bino needs to be tested over a few weeks while actually birding. Also, I am non-technical, so anything I say is “amateur user” opinion only, applying only to my eyes. I agree wholeheartedly with everything Dipperdapper says in the excellent review. Total cost to my door (in Ireland) was 368 euro, inclusive of 68 euro customs charges, plus postage. Communication and tracking details from Kevin in Oberwerk was excellent. At first, I was dismayed when I lifted the box…it felt heavy. But when I removed the packaging, and held the binos in my hand, they didn’t actually feel that heavy because the ergos and balance are excellent. Not unlike my Nikon SE 10×42, but about 50g heavier. The Oberwerk certainly is a tough, tank-like bino, feels very solid and durable. I like the longer objective barrels because I can get two fingers around them, as with the SE 10×42, and I find this helps further with stability. The objectives are deeply recessed, another feature I like because I presume they are more protected from stray light or damage. The focus wheel is stiffer than I would like, but I reckon this is the price you pay for a waterproof porro, like the Habicht 8×30. Although it is a wide wheel (see OPs photos), I find it a little difficult to get my fingers to it, and prefer the position of the FW on the Nikon 10×42. (OTOH, the diopter adjuster is on the right ocular, where the Binocular God intended….easy to adjust, but also firm enough to stay put). In any case the focusser has no play and turns smoothly. Eyecups twist in and out and have four positions. The bino came with a strap for the case, plus two straps for the bino…a lighter “stretchy” neoprene one for comfort, or a tougher fabric-type one. Try as I might, I could induce no CA, even looking against bare tree branches against a bright, high-cloud Irish February sky. In this it was the equal of my Zeiss TFL 8×32, which is excellent. The FOV (8.2 degrees) is similar, and to be honest it was sharp across most of the field, to the extent that to find any softness at all, I almost have to stick my eyeball into the bino and search sideways! In other words, the field-flattener question is a non-issue. I tried to induce flare/glare, and couldn’t manage that either, even while looking as close to the lightly-clouded sun as was possible without endangering my eyesight. I have no idea how to “measure” light transmission, but it seems plenty bright, not quite as bright as my TFL 8×32 but that’s unsurprising. I’m going to stick my neck out a bit here and say that I think the sharpness/constrast/pop (I don’t know how to separate these “concepts”) might be a little ahead of the TFL. However, this may be just because of today’s conditions, or I may be suffering from “new-bino enthusiasm”….it needs a bit more study out in the field, in different lighting conditions. The warranty is two years, but it feels like a bino that will be used by my as yet non-existent grandchildren. An interesting feature is that in the plain black box (thank you Oberwerk, no expensive fancy boxes!), there is a card headed “Quality Checklist”, with Date, Sale, SN etc., and all the features ticked off (under the headings Appearance, Mechanical, Alignment/Collimation, Resolution) and initialled “KGB” (whom I presume is Kevin rather than the defunct Soviet body). I’ll take these out and about over the next few weeks, and play with them a bit more, but I think they are a pretty stunning binocular at any price, and for 368 euro delivered a no-brainer, unless you favour roofs and very light binos.

Source: Birdforum link post #17

Furthermore, Sancho followed up with this post some months later:

Hi just reporting back on the Oberwerk SE 8×32, after four months of use. You know how it is, you never “really” know until you’ve used binos in the field in various conditions. I have to say these have become my favourite “all-rounder, grab n’go” binoculars, and my closet contains original SEs and some big European badges. I thought early on there was a bit of “play” in the focus, but there isn’t, it just focusses at different speeds as you turn the dial (if that makes sense). It is the best bino I have at suppressing CA and stray light, and the image has the punch and contrast that reminds me of my old (sadly sold) Nikon EDG 8×42. I love the stereopsis (3D?) effect of porros, so that’s a plus for me. I’m sorry I don’t have the technical vocabulary for talking about optics; I just love these and am thinking of buying the Oberwerk SE 10×42 to complement them.

Source: Birdforum link post #117

Another experienced observer, ‘Paultricounty,’ also offered his opinion on the 8 x 32 SE:

“These are bright and sharp binoculars. I’m going to get in trouble here with some Nikon guys, but they are brighter and at least as sharp as the Nikon SE’s. They’re more neutral in color than the Nikons and has a much wider field of view. There is no field flattener like the Nikons , so they’re not sharp to the edge. It’s a very usable FOV with fall off starting at around 75% , but no mushy edges like the Kowa BDII 6.5 and 8x and some other MIC bins. Contrast is as good as the Nikon and I couldn’t see the slightest amount of CA, clearly superior to the Nikon in that area.”

Source: Birdforum link post #83

Swiss binocular enthusiast Pinac, had this to say about the same instrument on the Oberwerk website:

I ordered one online at Oberwerk in Dayton OH on a Thu midday, Oberwerk dispatched the same day, and I got the SE at my home in Switzerland after 3 business days – not bad (for Oberwerk customer service and UPS)! I had been forewarned by the various reviewers that the SE is quite big and heavy for a 8×32 – it is indeed, but build quality and finish are excellent, and ergonomics are superb, the bino fits snugly into my hands, a joy to use. The immediate impression is that for a 250 $ bino, the optics are really good.

My sample actually magnifies 8.2 x. The measured RFOV and AFOV values are a bit narrower than specified by Oberwerk, but still very nice.

Plenty of eye relief; spectacle wearers should be fine.

Nice extra travel of the focus wheel of ca. 5 dpt beyond the infinity position.

Given that the number of available good 8×30 / 8×32 porro binos is continually shrinking, this is a very welcome additon to the binoculars market, not only for porro enthusiasts.

Source: Oberwerk Website Review# 2

And yet another review from a gentleman named Noah Lawes, who compared it to his Leica BN 8 x 42:

I’m extremely impressed with the 8×32 SE. It provides a beautiful, sharp, sparkling view. It compares favorably with my Leica BN 8×42, and it’s even better in some ways, including CA control, ergonomics, and handheld stability (especially when using the “hat trick” resting the bill of a cap on the prism housings. I’m working on a longer review which I plan to post on one of the forums, but for now, suffice it to say that I think this is a great binocular in absolute terms, and it’s just amazing that you can get it for $250.

Source: Oberwerk Website Review#4

It was also very favourably reviewed by the experienced Italian binocular enthusiast, Piergiovanni Salimbeni, who stated that its performance was similar to roof prism models costing €1K. Be sure also to check out the extensive video footage he captured through the instrument on his accompanying YouTube presentation.

Having said all that, I must report one additional observation regarding the instrument’s field of view. It was after comparing it to the Oberwerk Sport ED 8 x 42 that I noted its smaller field of view in comparison. Indeed, I conducted a star drift measurement and found its field of view to be 7.48 angular degrees, which is actually the same as the Nikon SE 8 x 32. Curiously, this was also noted by CNer Rustler 46 in this link.

I fixed the problem I had with the wandering dioptre, simply by securing my preferred position with a drop of Loctite superglue – problem solved!

Finally, I suggest a few improvements to the instrument:

Please don’t be discouraged concerning the undeserved attacks Oberwerk has endured regarding its Chinese manufacture. Is not China a sovereign nation, just like all the other nations under the sun? Does it not have people? I note that most of the negativity came from folk who never experienced the instrument first-hand. Indeed, I suspect from the sheer volume of views that many of these dissenters actually ended up secretly purchasing the instrument lol!

In summary, it’s no exaggeration that the Oberwerk SE 8 x 32 is destined to become one of the great 32mm binoculars of our time. It’s all the more remarkable that you were able to bring it to market at such an attractive price point, which resonates well with my key objective to provide the reader with genuine bargains in today’s market in order to grow this wonderful hobby worldwide.

I wish you continued success with this amazing product!

Sincerely,

Neil English PhD.

Author of the new book, Choosing & Using Binoculars: A Guide for Stargazers, Birders & Outdoor Enthusiasts, which will soon be published by Springer Nature.

Binoculars of any size benefit from stabilisation.

Could the Oberwerk Series 2000 heavy duty Monopod with trigger-grip head be the ultimate in stabilised viewing comfort?

Tune in soon for full details……..

The GPO Passion ED 10 x 32 package.

A Work Commenced December 18 2021

Instrument: German Precision Optics(GPO) Passion ED 10 x 32

Country of Manufacture: China

Field of View: 105m@1000m(6.0 angular degrees)

Exit Pupil: 3.2mm

Eye Relief: 15mm

Chassis: Rubber armoured magnesium alloy, machined aluminium eyecups

Close Focus: 2.5m advertised, 1.92m measured

Dioptre Compensation: +/- 2.5

Nitrogen Purged: Yes

Waterproof: Yes(1m un-stated time)

Coatings: Fully broadband multi-coated, phase and dielectric coatings applied to Schmidt Pechan roof prisms

ED Glass: Yes

Light Transmission: 90%

Tripod Mountable: Yes

Weight: 500g advertised, 509g measured

Dimensions: L/W 11.8/11.8cm

Accessories: cleaning cloth, hard case, neoprene neck strap, hard case strap, objective covers, ocular covers

Warranty: 10 years

Price: £352.99(UK)

In a previous blog, I reviewed the magnificent GPO Passion HD 10 x 42, one of the flagship models from the relatively new firm, German Precision Optics. For the money, I felt it was an excellent bargain, especially when compared to significantly more expensive models from Zeiss, Leica and Swarovski. Gone are the days when you have to shell out several grand to get a world class binocular, and in my opinion, GPO are definitely leading the way in this regard.

But having enjoyed the instrument for a couple of weeks, reality began to bite. As I’ve remarked before, the 42mm format is not my favourite. It has nothing to do with optics or ergonomics. It’s about weight. You see, I’ve come to strongly favour smaller formats. I already own and frequently use a world-class pocket binocular, the Leica Ultravid BR 8 x 20, but my experiences with larger binoculars convinced me that an optimum size for me would come from the compact class of binoculars, with apertures in the 30-35mm size class. Such instruments are easier to hold, easier to view through, and have more light gathering power. But I was also on the look out for a 10x instrument, to afford greater reach for my glassing targets, especially birds. While I’ve enjoyed some really high quality 10 x 25 pocket glasses in the past, their smaller objectives let in less light – an important parameter when glassing in shady areas during daylight hours, and especially for discerning subtle colour tones.

Unfortunately, GPO did not offer a smaller model in their flagship HD range, but they did have a 10 x 32 model from their more economical Passion ED line. After doing some research on this model(see the Preamble link above), I decided to pull the trigger and ordered one up for testing; enter the GPO Passion ED 10 x 32.

The GPO Passion ED 10 x 32 and its high quality carry case.

First Impressions

Costing less than half the price of the larger 10 x 42 HD model, the GPO Passion ED 10 x 32 package arrived with all of the same great quality accessories that delighted me in the larger HD binocular: I received the same neck strap, a smaller clamshell case, snugly fitting rain guard and objective lens covers, GPO-branded microfibre lens cleaning cloth, instruction manual and warranty card. It arrived in the same high quality presentation box as the larger HD model, with its unique serial number etched into the underside of the binocular and on the outside of the box. Very neat!

The GPO Passion ED 10x 32 has the same excellent build quality as the larger HD models.

Picking up the binocular and holding it, I was chuffed to see how well it fitted my hands. The narrow, single bridge allowed me to wrap my fingers round the barrels better than any other 30-32mm model I’ve previously handled. And while the instrument has a lovely, solid feel about it, with its sturdy magnesium alloy chassis, I was very reassured by its considerably lower weight; just 500g as opposed to ~ 850g for the larger, HD instrument.

The GPO Passion ED 10 x 32 fits perfectly in my hands!

The central hinge is nice and stiff, making it difficult to change the IPD on the fly. I like that. The binocular has a rather oversized central focus wheel, just like the heavier HD model, and I was relieved to see that it moved very easily and smoothly, with just one finger. The professionally machined aluminium eyecups are, in my opinion, even more impressive on the Passion ED model than the HD, rigidly locking into place with one intermediate click stop. The immaculately applied rubber armouring has two textures, just like the HD, a roughly textured side armouring and a silky smooth substrate covering the inside of the barrels.

All in all, very impressive!

Ergonomics

The GPO Passion ED shares many of the high quality ergonomic features built into the more expensive HD models. The ocular and objective antireflection coatings are immaculately applied and have a fetching magenta hue when observed in broad daylight. Unlike the HD models however, they do not have the hydrophobic coatings – an acceptable sacrifice, and then some.

Ocular lens end of the GPO Passion ED 10 x 32.

The objective lenses are recessed to an extent I’ve not seen before on any other compact model I’ve had the pleasure of using. I measured it at about 9mm! Why so deep? Well, it could be to protect those objectives from the vagaries of the weather; rain, wind, and stray light etc, or maybe partially compensating for the lack of hydrophobic coatings on the glass? Whatever the precise reason, I liked it!

The beautiful magenta coloured antireflection coatings on the Passion ED are immaculately applied, and note the exceptionally deeply recessed objective lenses!

The eyecups are beautifully designed; absolutely world class! They extend upwards with one intermediate position between fully retracted and fully extended, and lock into place rigidly with a reassuring ‘click.’ This is one binocular you can safely store inside its case with the eyecups fully extended for quicker deployment. They ain’t gonna budge!

Eye relief proved perfect for me, as I don’t use eye glasses, but I think the stated value of 15mm might be a bit optimistic, as I was not easily able to observe the full field of view keeping the eyecups down and wearing my varifocals.

The beautifully machined aluminium eyecups are world class, clicking into place with absolute rigidity.

Unlike the more expensive HD models which have a centre-locking dioptre adjustment, the Passion ED presents a more cost-effective solution by returning it to under the right ocular lens. While adjusting it, I noted its excellent rigidity, rendering it very resistant to accidentally moving while in the field. I felt it was a very acceptable compromise. Furthermore, the + and – settings are clearly marked, and so it’s very easy to memorise its optimal positioning should the instrument be used by others.

The oversized focus wheel is very easy to access and manoeuvre using one finger. It has a very grippy, texturized rubber overcoat, identical in fact to the more expensive HD models. Taking just over one complete turn to go from one extreme of its travel to the other, I would rate its speed as very fast; a good thing in my opinion, as it will be used primarily for birding, where big changes in focus position are often required following a mobile avian target. Motions are very smooth though, but I did notice a very small bit of play with it; similar in fact to focus wheel on the Leica Trinovid HD 8 x 32 I used and enjoyed a while back. Here the HD model came out better in my opinion, as I was unable to detect any play whatsoever with the 10 x 42.

I was most highly impressed with the way the binocular felt in my hands though. In truth, I don’t recall enjoying wrapping my medium sized hands around the barrels as much as on any other compact binocular I’ve tested. I reckon that this is attributed to the narrow bridge, which exposes those long, slender barrels. It’s simply a joy to hold, perfectly stable and always a thrill to bring to my eyes!

All in all, the build quality and handling of the Passion ED 10 x 32 are absolutely unrivalled in this moderate price class. GPO has clearly gone well beyond the call of duty in the design and execution of these new, highly-advanced compact binoculars!

Optics

The GPO Passion ED 10 x 32 came perfectly collimated. I was able to ascertain this by carefully focusing the binocular on the bright star Capella and then moving the right eye dioptre to the end of its natural travel. The perfectly focused star from the left barrel was found right in the centre of the defocused star diffraction pattern.

The lady reviewing the 10 x 32 in the Preamble to this review stated that the binocular had no issues with internal reflections and stray light and I was able to affirm this in the 10 x 32 I received. The image of an intensely bright beam of light from my IPhone torch was clean and devoid of diffraction spikes.

The exit pupils are nice and round and have little in the way of light leaks immediately around the pupil; a very good result but not quite in the same league as those found on the more expensive Passion HD 10 x 42.

Left eye pupil.

Right eye pupil.

In broad daylight, the images served up by the GPO Passion ED are very impressive! It is bright and very sharp across the entire field, with very little in the way of distortion even at the field stops. Like the Passion HD model, it enjoys a very decisive snap to focus on whatever target I turn it on. The small exit pupil ensures that the best part of your eye does all the imaging. Colours are vivid and natural but to my eye it has a slightly warm tone, with greens and browns coming through very strongly. Contrast is very good but not quite in the same class as the GPO Passion HD 10x 42 I tested it against. Glare suppression was also impressive. Comparing it to my control binocular – a Barr & Stroud Series 5 8x 42 ED – which exhibits excellent control of all types of glare, including veiling glare, the little Passion ED proved to be slightly superior to it. However, it was not quite as good in this capacity as the GPO 10 x 42 HD model, which exhibits the best control of glare that I have personally witnessed in any binocular.

Close focus is considerably better than I had expected. The accompanying user manual claimed 2.5m for this model, but I measured it at only 1.92m!

Colour correction in the GPO Passion ED 10 x 32 is very impressive! Pointing the binocular into the branches of a leafless tree against a bright overcast sky, the centre of the image is completely devoid of it, and even off axis, I could only coax the merest trace and only near the field stops. Returning to testing the binocular under the stars, I was able to verify just how well corrected the field of view is. Stars remain nice pinpoints nearly all the way to the edges. I attribute this excellent result to GPO’s optical engineers’ choice of field size. 6 degrees is not large by modern standards so it’s easier to achieve optical excellence using standard eyepiece designs. More on this a little later.

Venturing out on a freezing, misty December night to observe the full Moon, the GPO Passion ED 10 x 32 threw up a beautiful image. It was clean and sharp and contrasty. Secondary spectrum was non existent over the vast majority of the field, with only the extreme edges showing some weak lateral colour. Field illumination was also excellent, as with the 10 x 42 HD, with very little in the way of brightness drop off as the bright silvery orb was moved from the centre to the edge of the field. I also judged field distortion to be excellent in these tests too. The Moon remains razor sharp across most of the field, and only shows slight defocus at the field stops. Indeed, it was very comparable to the results I got with my optically excellent Leica Ultravid 8 x 20 in this regard.

Complementary instruments.

These are excellent results, and quite in keeping with the comments made by the lady from Optics Trade, as revealed in the Preamble video linked to at the beginning of the review. Indeed, these results place the GPO Passion ED in the top tier optically. Its colour correction was notably better than the Leica Trinovid HD 8 x 32, and I felt its sharpness and contrast were perhaps a shade better too. I’m confident that this 10 x 32 ED could hold its own against top-rated compact binoculars up to twice its retail value or more.

Notes from the Field & Concluding Comments

The view through the GPO Passion ED 10 x 32 is very stable and immersive. On paper a field of view of 105m@1000m might seem restrictive but in practice you never get that impression. There are no blackouts, rolling ball effects or any other issues common to compact models sporting wider fields of view with field flatteners. This makes panning observations particularly pleasurable with this instrument. To be honest, I suspected that this would have been the case after I had put the Passion HD 10 x 42 through its paces. Indeed I would hazard a guess that both binocular lines – the HD and ED – have substantially similar optical designs. As an experienced glasser, I have no abiding interest in very large fields of view. Indeed, I tend to think of those wide angle binoculars as rather distracting and more suited to beginners than more seasoned observers. I’m interested in vignettes not vistas.

Goldilocks Binocular.

So there you have it! The GPO Passion ED 10 x 32 is, for me, a Goldilocks binocular, serving my purposes perfectly and fitting my hands like a tailor-made glove. It pays to mention that GPO also market a 8 x 32 with a wider field of view, and two 42mm models with powers of 8x and 10x; so something for everyone! Check them out as soon as you can. You’ll not be disappointed!

Dr Neil English has some exciting news to reveal early in the new year. For now, he’d like to wish all his readers a Very Happy Christmas!

Plotina: the author’s modified 130mm f/5 Newtonian reflector, with a Vixen Erecting Adaptor and two simple Plossl eyepieces used in the investigation.

A Work Commenced October 3 2021

In this blog, I’ll be demonstrating the potential of a small Newtonian reflector operating in spotting ‘scope mode. This follows on from a previous blog I conducted to find a suitable optical device that would give fully erected and correct left-right orientation, just like a conventional spotting scope.

First, a few words of introduction about the telescope. It’s a 130mm f/5 SkyWatcher Newtonian reflector, so has a focal length of 650mm. Because of its open-tube design, the instrument is surprisingly light; just 3.8 kilos(8.4 pounds) and 4.1 kg (9 pounds) with the mounting bracket attached. It acclimates fully in 30-40 minutes, even when taken from a warm indoors environment to the cold of a Winter’s day. But such thorough cooling is only necessary to coax the highest powers out of the instrument.

The instrument has mirrors treated with state-of-the-art Hilux coatings(applied by Orion Optics, UK), increasing its overall reflectivity to 97 per cent. The primary mirror is the original one supplied by SkyWatcher, while the secondary flat mirror was upgraded with an Orion Optics UK secondary, having a flatter surface and smaller semi-major diameter of 35mm. This provides a small 26.9 per cent central obstruction. This size of central obstruction is significantly smaller than a Maksutov or Schmidt Cassegrain (SCT) of the same aperture. Unlike the popular Maksutov, the 130mm Newtonian(aka Plotina), can deliver a significantly lower magnification. For example, using a 32mm Skywatcher Plossl, it delivers a power of just 20x and using another Plossl of focal length 10mm, the telescope provides an amplification of 65x. I used these two eyepieces to demonstrate the spotting scope potential of the Newtonian, as many conventional spotters provide magnifications in this range(20-65x), corresponding to exit pupils of 4.7 and 2mm, respectively.

The contrast transfer is provided by subtracting the aperture of the secondary from the primary(130-35 = 95mm), thus one can expect a degree of contrast equivalent to a 95mm apochromatic refractor. Its light gathering power and resolution(0.89″) are significantly higher than a 95mm refractor, however. This has been borne out in several years of observations of lunar, planetary, double star and deep sky observing. The reader will find several other blogs I have published on this instrument in the past by clicking on the ‘Telescopes’ link on the home page.

The Erecting Adapter: Purchased for £80, the Vixen erecting adapter is a rather long appendage but delivers an upright image with the correct left-right orientation, just like a conventional spotting ‘scope. The lenses in the adapter are fully multi-coated and truncates the field a little when employing longer focal length eyepieces. You simply insert the desired eyepiece into the adapter, focus the ‘scope, and you’re off to the races!

Plotina, with the erecting adapter attached.

The instrument was used in broad daylight outside on a cool, breezy autumnal day, between heavy rain showers. It was mounted on a simple non motorised alt-azimuth(Vixen Porta II). The instrument is equipped with Bob’s Knobs screws for quick and easy collimation using a Hotech laser collimator. Alignment of the optics takes just a few seconds to get precise alignment of the secondary and primary mirrors. All of the images were taken simply by pointing my Iphone 7 into the eyepiece and taking single images. The pictures presented here are the highest resolution I can load onto this website( ~200-750KB), so are not the highest quality that I can potentially show. All the images are completely unmodified, apart from cropping. All distances quoted were measured with a laser range finder, and all the images were taken on the same breezy afternoon of October 3 2021.

Results:

Image 1: Shows a TV satellite dish at a power of 20x located at distance of 27 yards:

Image 2 shows some autumn leaves at 20x and located at a distance of 18.9 yards

Image 3 shows the branches of a tree at 20x located 43.1 yards from the scope:

Image 4 shows a hill top located at about 2 km distance at 65x

Discussion:

I am very encouraged by the results I obtained this afternoon. Irrespective of the scepticism of arm chair theorists, the images speak for themselves! The instrument provides very nice, high contrast and colour pure renditions of a variety of targets. Chromatic aberration is particularly well controlled, as expected, given that the Newtonian is a truly apochromatic optical system, though some secondary spectrum is introduced by the eyepieces chosen. In addition, higher quality eyepieces will give better off-axis performance, and because those oculars are inter-changeable, a greater range of magnifications can be explored. Visually, the images are considerably better when examined with the naked eye. The reader will note that these magnifications are somewhat pedestrian for such a large telescope. Visually, much higher magnifications can be utilised profitably. And although the formidable resolving power of the instrument is clearly in evidence, the images could be improved further by employing a higher quality phone camera. What’s more, the images could also be processed lightly to bring out even more details.

The set up, though admittedly bulky by conventional spotting scope standards, could quite easily be erected in the field or, better still, in a hide, where it could be used to gather video footage or still images with the right equipment. Observing from indoors, through a clean window is also a distinct possibility, especially at lower powers. The instrument is not weatherproof however, owing to its open-tube design, so may be prone to dewing up but a small, battery-operated fan would extend its longevity in field use.

I believe this provides a very cost effective way(the entire apparatus set me back just a few hundred pounds) of obtaining high quality images compared with a high-end apochromatic spotter.

Food for thought!

Thanks for reading!

Dr Neil English spent most of his adult life testing and observing through telescopes of all varieties and genres. He now enjoys a new lease of life exploring the terrestrial realm during daylight hours.

De Fideli.

I will praise thee; for I am fearfully and wonderfully made: marvellous are thy works; and that my soul knoweth right well.

Psalm 139:14

In this series of lectures, world-leading synthetic organic chemist, Professor James Tour, takes on an internet troll who claims that scientists have discovered how life got started from simple chemicals on the primordial Earth. In this series of presentations, Dr. Tour explains, in exquisite technical detail, why scientists are really clueless about how life got started.

Indeed, abiogenesis is actually impossible!

So buckle up and enjoy the ride!

An Introduction to Abiogenesis

The Building Blocks of Building Blocks

Chiral-Induced Spin Selectivity

Cell Construction & Assembly Problem Part 1

Cell Construction & Assembly Problem Part 2

“Escaping the Beginning? Confronting Challenges to the Universe’s Origin.

Did the universe have a beginning—or has it existed forever?

If the universe began to exist, then the implications are profound. Perhaps that’s why some insist it has existed forever.

In Escaping the Beginning?, astrophysicist and Christian apologist Jeff Zweerink thoughtfully examines the most prevalent eternal-universe theories—quantum gravity, the steady state model, the oscillating universe, and the increasingly popular multiverse. Using a clear and concise approach informed by the latest discoveries, Zweerink investigates the scientific viability of each theory, addresses common questions about them, and then focuses on perhaps the most pressing question for believers and skeptics alike: If the evidence continues to affirm the beginning, what does that imply about the existence of a Beginner?

About the Author: Jeff Zweerink (PhD, Iowa State University) is an astrophysicist specializing in gamma-ray astrophysics. He serves as a senior research scholar at Reasons to Believe and as a part-time project scientist at UCLA. He has coauthored more than 30 papers in peer-reviewed journals and numerous conference proceedings.

Some Reviews Thus Far Garnered:

“In Escaping the Beginning? Jeff Zweerink leads the reader through a fascinating tour of the scientific development of the big bang theory as well as the theological and philosophical implications of the beginning of our universe. More importantly, he addresses some of the recent speculations by scientists that attempt to circumvent both a beginning and a Beginner and shows that the best current scientific evidence continues to point to an actual beginning of our universe. The hypothesis that the universe came into existence through the actions of a transcendent intelligent Creator is still arguably the explanation that best fits the scientific data.”

—Michael G. Strauss, PhD

David Ross Boyd Professor of Physics

University of Oklahoma

“As an atheist detective investigating the existence of God, I hoped the evidence would reveal an eternal universe without a beginning because I knew the alternative would be hard to explain from my atheistic worldview. . . . Escaping the Beginning? examines the evidence for the universe’s beginning and the many ways scientists have tried to understand and explain the data. I wish I had his important book when I first examined the evidence. If I had, I would probably have become a believer much sooner.”

—J. Warner Wallace

Dateline-featured Cold-Case Detective

Author of God’s Crime Scene

“There are few books I read twice. but this is one of them. Although understanding this book will take effort for anyone untrained in the sceinces, the effort is well worth it. Dr. Zweerink answered many of my questions about the existence of the multiverse, evidence for the beginning of the universe, and problems for common challenges to divine creation. . . . Escaping the Beginning? deserves wide readership by believers and skeptics alike.”

–Sean McDowell, PhD, Author of Evidence that Demands a Verdict

“Jeff Zweerink has done something I might have thought to be impossible. He has made cosmology accessible to scientific laypersons like me. Whether it’s quantum fluctuations, inflation theory, or the various models of the multiverse, Zweerink explains things clearly and with good humor. Even more importantly, he shows that the findings of modern cosmology give Christians even more reason to worship and adore our great God who created all things.”

-Kenneth Keathley

Senior Professor of Theology, Southern Baptist Theological Seminary.

“Does the universe have a beginning, or has the physical realm existed forever? This is an ancient question and still hotly debated today. The interest in the subject is not just from its obvious scientific significance, but also from its religious implications. Since the first cosmological and theoretical evidence for a universe with a distinct beginning was discovered a century ago, some of the most intense opposition among scientists to the notion of a beginning has been primarily on religious grounds. In this engaging book, Jeff Zweerink reviews the state of the theory and experiment, and argues that far from having been escaped, a bginning to the universe is the likely outcome of the current lines of research.”

-Bijan Nemati

Principal Research Scientist, University of Alabama in Huntsville.

“Did the universe have a beginning? If so, what would that imply? Does the origin require an Originator? Does a creation imply a Creator? What would that mean for our lives?

Paul Valery once said, “What is simple is wrong, and what is complex cannot be understood.” Dr. Zweerink splits the horns of this dilemma by raising many of the issues surrounding a cosmological beginning in an enjoyable and accessible format for a general audience. yet this is done without sacrificing the critical details that attend the state-of-the-art.

He draws on his training and expereince as an astrophysicist to unpack the history of the big bang, its blossoming into the universe around us, and otther topics of fascination, interest, and wonder. Dr. Zweerink then goes to the heart of contemporary cosmology to find out what today’s cosmologists – our secular priests -are saying about cosmic origins.

While I might believe the scientific case for a beginning and a Creator is a bit stronger than Jeff does, his grasp of the issues and presentation style will serve his audience well.”

-James Sinclair

Senior Physicist, United States Navy.

“I had the privilege of debating Jeff Zweerink on two occasions. As an atheist, I was surprised to see how much common ground there was between us. And that is because Jeff is an incredibly honest and thoughtful person and his writing reflects that. Escaping the Beginning? is a well-written and carefully researched work that doesn’t shy away from challenges to cherished belief and deserves to be widely read by the community. It does what a good book should do—educate and (I hope) stimulate thoughtful debate.”

—Skydivephil

Popular YouTuber and Producer of the Before the Big Bang Series

Featuring Exclusive Interviews with Stephen Hawking, Sir Roger Penrose,

Alan Guth, and Other Leading Cosmologists

Seeing Scripture through Jewish eyes.

A song: a psalm of Asaph.

God, do not keep silent.

Do not hold Your peace, O God.

Do not be still.

For look, Your enemies make an uproar.

Those who hate You lift up their head.

They make a shrewd plot against Your people,

conspiring against Your treasured ones.

“Come,” they say, “let’s wipe them out as a nation!

Let Israel’s name be remembered no more!”

For with one mind they plot together.

Against You do they make a covenant.

Psalm 83: 1-5

Are you looking for a brand-new Bible experience? Are you searching for a translation of the Bible that restores some of the Hebrew names and terminology found in the original manuscripts? Perhaps you are looking for a Bible that will help you rekindle an interest in the sacred words of Scripture seen from a Messianic Jewish perspective? If so, I have just the recommendation for you; enter the Tree of Life Vesion(TLV).

The brain child of this ambitious project was Daniah Greenberg and her Rabbi husband, Mark Greenberg, who assembled a cadre of Messianic Jewish Bible scholars to create an all-new translation of the Holy Scriptures that gives the reader a solid flavour of the original Hebraic overtones of the Bible, with a decidely Jewish accent. But it was no small feat, given the proliferation of English Bible versions flooding the global market. Daniah had the courage and conviction to raise the funds to pay for soild scholarship within the Jewish cultural tradition, which culminated with the first edition of the TLV Bible in 2011. Daniah Greenberg now serves as President of the Messianic Jewish Family Bible Society. Greenberg is also CEO of the newly established TLV Bible Society.

It pays to remember that all the Biblical writers, with the possible exception of the author of the Book of Job, were Jews. Jesus Christ was Jewish. The earliest Christian meetings took place in synagogues and despite the attendant evils of anti-semitism throughout history, and its giving rise to unbiblical ideas such as replacement theology, it is undoubtedly the case that unique insights into much of the Biblical narrative has come from the Jewish mindset. Seen in this light, it is not at all surprising that a new Bible translation made by the original people to which the Lord of all Creation first appeared should find a place on the bookshelves of many Christians in the 21st century.

The first thing you will notice about the TLV is the unfamiliar ordering of the books of the Bible, which have been re-presented in the order rendered in the Jewish tradition, which Christians refer to as the Old Testament. In Jewish parlance, these are the books of the Tanakh.

As you can see from the table of contents below, the Tanakh is further divided into three sections; the Torah (Law of Moses or Pentateuch), the Neviim (The Prophets) and the Ketuvim (The Writings).

The unique ordering of the books of the Old Testament(Tanakh), as experienced by Orthodox Jews.

The books of the New Testament(Good News) are presented in their traditional order. The reader will note that the Book of James is titled ‘Jacob,’ and Jude is titled ‘Judah, which represent their transliterated Jewish names.

The New testament books are presented in their traditional order, with two transliterated names, Jacob(James) and Judah(Jude).

A sizeable number of words are presented in the original Hebrew. For example, YHWH God’s covenant name, is often referred to as Adonai, but also as Elohim (Creator). Jesus is denoted as Yeshua, Mary(the mother of Jesus) is given her original name, Miriam; Spirit is presented as Ruach, the Levitical priests, Kohanim, the children of Israel, B’nei-Israel and Sabbath is translated as Shabbat. All Hebrew terminology can be referenced at the back of the Bible in the form of a tidy glossary. There is even a section which helps the reader pronounce these Hebrew words correctly. That said, once you get into the TLV, most of the terms sink in very easily and naturally and so provide the reader with an education in basic Hebrew religious terminology. The addition of original Hebrew words also adds to the poetic beauty of the language of the Scriptures, which are readily appreciated while reading through.

Each book of the Holy Scriptures is accompanied by a short introduction written by Messianic Jewish scholars, which provides a concise overview of the most important ideas developed in the texts. The translators intentionally chose to produce a translation that is at once respectful to more traditional translations of the Bible such as the Authorized King James Version (KJV), and more modern translations such as the English Standard Version (ESV) and New American Standard Bible (NASB), retaining some classic Biblical terminology such as “Behold“, “lovingkindness” and “Chaldeans.” For example, in the opening verses of the Book of Esther, the TLV refers to the Babylonian King as Ahasuerus and not Xerxes ,as you will find in looser translations such as the NIV and NLT.

This is what happened in the days of Ahasuerus, the Ahasuerus who reigned over 127 provinces from India to Ethiopia.

Esther 1:1

In keeping with the original customs of the first Christians, the word ‘baptism‘ does not appear in the TLV, being replaced by the more appropriate term, ‘immersion.’ This is entirely justified as infant baptism was not practiced by the earliest followers of Yeshua. Consider this passage from Acts 2;

Peter said to them, “Repent, and let each of you be immersed in the name of Messiah Yeshua for the removal of your sins, and you will receive the gift of the Ruach ha-Kodesh.

Acts 2:38

John the Baptist is likewise referred to as “John the Immerser”

Unlike virtually all other Bibles in the English language, the Adversary’s name is presented in lower case, ‘the satan‘; a most appropriate demotion to honour the ‘father of lies.’ Consider, for example, the opening passages of the Book of Job:

One day the sons of God came to present themselves before Adonai, and the satan also came with them. Adonai said to the satan, “Where have you come from?”

The satan responded to Adonai and said, “From roaming the earth and from walking on it.

Adonai said to the satan, “Did you notice my servant Job? There is no one like him on the earth—a blameless and upright man, who fears God and spurns evil.”

Job: 1:6-8

Another interesting aspect of the TLV is that it quite often departs from the usual preterite, or imperfect tense one normally experiences in traditional translations. Consider this passage from the Gospel of Matthew Chapter 4 in the NASB:

Again, the devil took Him to a very high mountain and *showed Him all the kingdoms of the world and their glory;

Matthew 4:8

Now consider the same passage in the TLV:

Again, the devil takes Him to a very high mountain and shows Him all the kingdoms of the world and their glory.

Matthew 4:8

These occasional departures add to the immediacy of the situation as if it were happening right now! This is a powerful linguistic tool that the TLV scholars used to evince the poignancy of certain passages of Holy Scripture.

The poetic books of the Holy Scriptures, such as the Psalms, are most beautifully rendered and retain traditional terms like Selah (an uncertain word thought to refer to an interlude in a musical performance). Consider, for example, Psalm 24 in the TLV:

A psalm of David.

The earth is Adonai’s and all that fills it—

the world, and those dwelling on it.

For He founded it upon the seas,

and established it upon the rivers.

Who may go up on the mountain of Adonai?

Who may stand in His holy place?

One with clean hands and a pure heart,

who has not lifted his soul in vain,

nor sworn deceitfully.

He will receive a blessing from Adonai,

righteousness from God his salvation.

Such is the generation seeking Him,

seeking Your face, even Jacob! Selah

Lift up your heads, O gates,

and be lifted up, you everlasting doors:

that the King of glory may come in.

“Who is this King of glory?”

Adonai strong and mighty,

Adonai mighty in battle!

Lift up your heads, O gates,

and lift them up, you everlasting doors:

that the King of glory may come in.

“Who is this King of glory?”

Adonai-Tzva’ot—He is the King of glory! Selah

Psalm 24

The reader of the TLV Holy Scriptures will note that the word “church” does not appear in this translation. Instead, the scholars chose to use the words “Messiah’s community.” This is an acceptable change, as the word they were probably translating was the Greek term ecclesia, which appears in the New Testament 115 times and was often associated with a civil body or council summoned for a particular purpose. The nearest the Greek language gets to “church” is kuriakos, which is best understood as “pertaining to the Lord,” which probably morphed into the Germanic “Kirche” or “Kirk,” which is still used in northern England and Scotland to this day.

An amusing aside: Has anyone ever referred to Kirk Douglas as ‘Church Douglas’, who just happens to be an orthodox Jew?

These translative nuances matter little in the scheme of things however. Acts 11 provides a good illustration of these translation choices:

Then Barnabas left for Tarsus to look for Saul, and when he had found him, he brought him to Antioch. For a whole year they met together with Messiah’s community and taught a large number. Now it was in Antioch that the disciples were first called “Christianoi.”

Acts 11:25-26

Note also that the TLV translation team used the Greek term for Christians, ‘Christianoi‘. This is also perfectly acceptable, as there was no Hebrew word for ‘Christian’ in those early days.

The scholars who created the TLV chose to use the latest manuscript evidence, which included much older texts found in the modern era compared with the King James or New King James, for example(which are based on the Textus Receptus). It thus follows a similar translation ethos to other popular Bibles in the English language such as the NIV and ESV. On the spectrum of modern English Bible translations, which vary from the highly literal, so-called ‘word for word’ renderings, through the less literal ‘thought to thought’ translations, I would categorise the TLV as adopting a ‘middle of the road’ approach. Perhaps the best way to illustrate this is to look at the same passage of Scripture in a few translations. Consider, for example, the highly literal NASB rendition of Matthew 9, verses 1 through 8:

Getting into a boat, Jesus crossed over the sea and came to His own city. And they brought to Him a paralytic lying on a bed. Seeing their faith, Jesus said to the paralytic, “Take courage, son; your sins are forgiven.” And some of the scribes said to themselves, “This fellow blasphemes.” And Jesus knowing their thoughts said, “Why are you thinking evil in your hearts? Which is easier, to say, ‘Your sins are forgiven,’ or to say, ‘Get up, and walk’? But so that you may know that the Son of Man has authority on earth to forgive sins”—then He said to the paralytic, “Get up, pick up your bed and go home.” And he got up and went home. But when the crowds saw this, they were awestruck, and glorified God, who had given such authority to men.

Matthew 9:1-8(NASB)

Next consider the TLV equivalent:

After getting into a boat, Yeshua crossed over and came to His own town. Just then, some people brought to Him a paralyzed man lying on a cot. And seeing their faith, Yeshua said to the paralyzed man, “Take courage, son! Your sins are forgiven.” Then some of the Torah scholars said among themselves, “This fellow blasphemes!” And knowing their thoughts, Yeshua said, “Why are you entertaining evil in your hearts? For which is easier, to say, ‘Your sins are forgiven,’ or to say, ‘Get up and walk’? But so you may know that the Son of Man has authority on earth to pardon sins…” Then He tells the paralyzed man, “Get up, take your cot and go home.” And he got up and went home. When the crowd saw it, they were afraid and glorified God, who had given such authority to men.

Matthew 9:1-8(TLV)

Finally, consider the same passage from a thought for thought translation like the NIV:

Jesus stepped into a boat, crossed over and came to his own town. Some men brought to him a paralyzed man, lying on a mat. When Jesus saw their faith, he said to the man, “Take heart, son; your sins are forgiven.” At this, some of the teachers of the law said to themselves, “This fellow is blaspheming!” Knowing their thoughts, Jesus said, “Why do you entertain evil thoughts in your hearts? Which is easier: to say, ‘Your sins are forgiven,’ or to say, ‘Get up and walk’? But I want you to know that the Son of Man has authority on earth to forgive sins.” So he said to the paralyzed man, “Get up, take your mat and go home.” Then the man got up and went home. When the crowd saw this, they were filled with awe; and they praised God, who had given such authority to man.

Matthew 9:1-8(NIV)

I think it is reasonable to conclude that the TLV is a good compromise between both translation philosophies, distinguishing itself by means of introducing some Hebrew words and names but also in the way that the translators have chosen to alter the tense of some passages, as discussed previosuly.

The TLV also follows many of the newer Bible versions in adopting a more gender neutral approach to terms such as ‘Brethern’ or ‘Brothers’. For example, the TLV renders Galatians 1:11 thus:

Now I want you to know, brothers and sisters, that the Good News proclaimed by me is not man-made.

Galatians 1:11 (TLV)

Compare this to the more conservative ESV:

For I would have you know, brothers, that the gospel that was preached by me is not man’s gospel.

Galatians 1:11 (ESV)

And the NIV:

I want you to know, brothers and sisters, that the gospel I preached is not of human origin.

Galatians 1:11(NIV)

Some commentators have expressed concern that the Bible should never be altered so as to express political correctness, as in this case, where ‘brothers’ is altered for the sake of inclusiveness to read, ‘brothers and sisters.’ I understand their concerns but I have no strong opinion either way on this issue, so long as the context of the particular verse is not altered.

The TLV does have a couple of errors which I picked up while reading through the translation. The first appears in Jeremiah 34:14

At the end of seven years you are to set free every man his brother that is a Hebrew who has been sold to you and has served you six years; you are [to] let him go free from you.’ But your fathers did not obey Me, nor inclined their ear.

I have inserted the missing word in bold brackets that makes the sentence comprehensible.

In addition there is a printing error in my Large Print Personal Size TLV on page 902 and 903, the heading of which reads “Obadiah 9” and “Obadiah 1,” respectively. Since these headings are meant to illustrate the chapter numbers, they are clearly unecessary as the Book of Obadiah only has a single chapter.

The typographical error niggled me at first (as an avid reader, I’m very tolerant of typos in general but view Holy Scripture in a more exalted light), but I understand that these things happen. I have written to the TLV Bible Society informing them of these issues which I hope they will be able to resolve in due course.

Some comments on the physical presentation of the TLV Holy Scriptures

The author’s TLV large print copy of the Holy Scriptures.

I was very impressed with the quality of the giant print personal size TLV that I acquired back in January 2018. It has a beautiful leathertex cover, which is soft and durable. Indeed, the current selection of faux leather Bibles(in many translations)are amazing value for money, and are superior to the cheap, bonded leather found on premium Bibles just a decade ago. The TLV also has a Smyth-sewn binding for greater durability even with prolonged use.

The Personal Size Giant Print TLV is about 9 inches long and 2 inches thick.

It has a paste-down liner, a highly readable 12.5 font size, beautiful gold gilded pages and comes with a single ribbon marker. I especially like the paper used by Baker Books(the publisher of the TLV), which is a more creamy white than the usual white pages seen n many other of my Bibles. As seen below, the text is presented in a double column format and has a generous number of cross-references. The text is line matched and shows minimal ghosting, which annoys some people more than others.

The paper in the TLV is an off white(creamy), the text is double columned, shows little bleed-through, with clear 12.5 sized font.

The back of the TLV has an extensive concordance, a short glossary explaining the Hebrew terms used in the translation, as well as a short section of prayers (including the Aaronic benediction and the Lord’s Prayer) and other blessings for those who wish to learn a little more Hebrew. A couple of maps show Yeshua’s travels in the 1st century AD as well as a modern map of Israel. Best of all, you can acquire all of this for a very modest price: I paid about £25 for my copy but you can also get it at discounted prices from smaller retailers. See here for just one example.

I would highly recommend the TLV to avid readers of the Bible. It will come in especially handy when witnessing to Jews but can be enjoyed by anyone who appreciates the deep Hebrew roots of the Christian faith.

Dr Neil English shows how the Christain faith has inspired visual astronomers over the centuries in his new historical work; Chronicling the Golden Age of Astronomy.

Post Scriptum: You can also read the TLV(or indeed any other Bible translation) online by visiting BibleGateway.com

Some life scientists believe they can present a truly naturalistic scheme of events for the origin of life from simple chemical substrates, without any appeal to an intelligent agency.

Here is one such scenario, presented by Harvard professor, Jack Szostak.

I invite you to study the video at your leisure.

In this work, I wish to critically appraise each of the steps Dr. Szostak presents in light of the latest research findings that show that any such scheme of events is physio-chemically untenable from a purely naturalistic perspective.

Video Clock Time 00.00 -10.00 min

Here Dr. Szostak sets the scene for this thesis, exploring the varied landscapes and environments under which we find life on Earth. Dr. Szostak reasonably suggests that when life first appeared on Earth, it must have done so in an extreme environment with higher temperatures and in aqueous environments with extreme pH values and high salinity. What Dr. Szostak does not acknowledge is that life was already complex when the Hadean environment first cooled enough to permit life to gain a footing. For example, there is solid isotopic evidence that the complex biochemical process of nitrogen fixation was already in place at least 3.2 Gyr ago and possibly earlier still.

References

Eva E. Stüeken et al., “Isotopic Evidence for Biological Nitrogen Fixation by Molybdenum-Nitrogenase from 3.2 Gyr,” Nature, published online February 16, 2015, http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/nature14180.html.

“Ancient Rocks Show Life Could Have Flourished on Earth 3.2 Billion Years Ago,” ScienceDaily, published online February 16, 2015, http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/02/150216131121.htm.

In a more recent study conducted by a team of scientists headed by Professor Von Karnkendonk, based at the University of South Wales, solid evidence for complex microbial ecosystems in the form of stromatolite colonies were established some 500 million years earlier at 3.7 Gyr ago.

Reference

M..J Van Krankendonk et al, Rapid Emergence of Life shown by the Discovery of 3,700 Million Year Old Microbial Structures, Nature Vol 537, pp 535 to 537, (2016).

Dr. Szostak claims the origin of life must have occurred via a Darwinian evolutionary mechanism, but the self-evident complexity of the first life forms strongly argues against this assertion, as there would not have been enough time to have done so. In other words, the window of time available for the emergence of the first forms of life on Earth is too narrow to entertain any viable Darwinian mechanism.

Dr Szostak continues by considering the vast real estate available for potential extraterrestrial life forms. Szostak presents the emerging picture; the principle of plenitude – that of a Universe teeming with planets. That is undoubtedly the case; there are likely countless trillions of terrestrial planets in the Universe. However, new research on the frequency of gamma ray bursts (GRB) in galaxies suggests that such violent events would greatly hamper any hypothetical chemical evolutionary scenario. In December 2014, a paper in Physical Review Letters, a group of scientists estimated that only 10 per cent of galaxies could harbour life and that there would be a 95 per cent chance of a lethal GRB occurring within 4 kiloparsecs of the Galactic centre, and the likelihood would only drop below 50 per cent at 10 kiloparsecs from a typical spiral galaxy. What is more, since the frequency of GRBs increases rapidly as we look back into cosmic time, the same team estimated that all galaxies with redshifts >0.5 would very likely be sterilised. These data greatly reduce the probability that a planet could engage in prebiotic chemistry for long enough to produce anything viable.

Reference

http://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevLett.113.231102#abstract

In addition to GRB induced sterilization events, Dr Szostak completely ignores the remarkable fine tuning that is required to produce a planetary system that could sustain life for any length of time.

References

http://www.reasons.org/articles/fine-tuning-for-life-on-earth-june-2004

http://www.reasons.org/articles/fine-tuning-the-ratio-of-small-to-large-stars

Dr. Szostak entertains the possibility that lifeforms with fundamentally different chemistry may evolve and that our type of life might be the exception rather than the rule. This reasoning is flawed however, as the latest research suggests that carbon-based chemistry in a water-based solvent is overwhelmingly more likely to sustain any biochemical system throughout the Universe. Ammonia has been suggested as an alternative solvent to water but there are some(possibly insurmountable) issues with it.

References

http://www.reasons.org/articles/water-designed-for-life-part-1-of-7

http://www.reasons.org/articles/weird-life-is-ammonia-based-life-possible

Summary: Dr Szostak’s introduction presents a gross oversimplification of the true likelihood of prebiotic chemistry becoming established on Earth and other planets. Szostak does concede that our planet could be unique but is unlikely to be. The emerging scientific data however supports the view that life will be rare or unique to the Earth.

Video Clock Time; 10:00 – 32:00 min

The RNA World

In this section, Dr. Szostak presents the central dogma of molecular biology: DNA begat RNA and RNA begat proteins. Origin of life researchers were completely in the dark about how this scheme of events came into being, but in the mid-1980s, Thomas Cech et al discovered that RNA molecules could act catalytically.

Reference:

Zaug, A. J & Cech, T. The Intervening Sequence of RNA of Tetrahymena is an Enzyme, Science, 231, (1986).

This immediately suggested a way forward; perhaps RNA was the first genetic material and over the aeons, it gradually gave up these activities to its more stable cousin, DNA. Szostak gives some examples of how this ‘fossil RNA’ has been incorporated into structures like ribosomes, the molecular machines that carry out the synthesis of polypeptide chains. His interpretation of these examples as ‘fossils’ is entirely speculative, however.

Szostak then explores hypothetical loci where prebiotic synthesis of biomolecules could have taken place, including the atmosphere, at hydrothermal vents and on mineral surfaces. For the sake of clarity, let’s take a closer look at RNA nucleotides, and in particular, the pentose sugar, ribose. Dr. Szostak mentions the Urey-Miller experiments where supposed prebiotic molecules were produced when an electric discharge was passed through a reducing atmosphere including water vapour. Though widely cited in college textbooks, its validity has in fact, long been discounted by serious researchers in the field. Urey and Miller assumed the atmosphere to be reducing in nature, but it is now known that it was neutral, consisting of nitrogen, carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide and water vapour.

Reference:

The Early Setting of Prebiotic Evolution, Shang,.S

From Early Life on Earth, Nobel Symposium No. 84, Bengtson, S. (ed.), pp 10-23, Columbia University Press (1994).

Even in the complete absence of molecular oxygen, this atmosphere could not have sustained the production of prebiotic molecules, including ribose. Only in the presence of significant quantities of molecular hydrogen has some synthesis been demonstrated.

Reference:

Schlesinger, G, & Miller, S. Prebiotic synthesis in Atmospheres containing methane, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide. Journal of Molecular Evolution, 19, 376-82 (1983).

The problem with this scenario though is that molecular hydrogen would rapidly escape from the Earth’s gravitational field and thus is entirely irrelevant to the question of prebiotic synthesis.

An Aside:

Video Clock Time: 20:00 min: The Narrow Time Window: Reconciling Dr. Szostak’s timeline for prebiotic chemical evolution with impactor bombardment history.

At 20.00min on his video, Professor Szostak envisages the time during which prebiotic chemical evolution took place on the primitive Earth. He dates it to a period between 4.2 and 3.8Gyr ago (the supposed time of the beginning of the RNA world). Szostak presents a warm, aqueous environment during which all these reactions were taking place. But the planetary scientists modelling the impact history of the inner solar system have revealed a violent early history for the Earth. Extensive isotope analysis of terrestrial and lunar rocks, as well as cratering rate analysis indicate that the inner solar system was subjected to intense bombardment from the debris left over from the formation of the planets, which occurred between 4.5 and 3.9 Gyr ago. The cratering intensity declined exponentially throughout that era, except for a brief episode of increased bombardment between 4.1 and 3.8 Gyr ago. This is known as the Late Heavy Bombardment. One study has estimated that the total accumulation of extraterrestrial material on Earth’s surface during this epoch added a mean mass of 200 tons per square yard over all the surface of the Earth. Thus, Dr. Szostak’s relatively ‘gentle’ scenario is untenable. Realistically, the only oceans to speak of during this epoch are those of magma.

Reference:

Anbar A.D. et al, Extraterrestrial Iridium, Sediment Accumulation and the Habitability of the Earth’s Surface, Journal of Geophysical Research 106 ( 2001) 3219-36.

http://www.reasons.org/articles/no-primordial-soup-for-earths-early-atmosphere

Back to Ribose (a key component of RNA nucleotides discussed by Dr. Szostak). The only plausible mechanism for the synthesis of ribose is the so-called Butlerow reaction (also referred to as the formose reaction) which involves the coupling of the single carbon molecule, formaldehyde (methanal) in spark-ignited reactions, forming sugars of varying carbon numbers, including ribose. However, many side reactions dominate formose chemistry, with the result that the atom economy with respect to ribose is very low; up to 40 other chemical products being typically produced. This is the case in carefully controlled laboratory synthesis (read intelligently designed!), where the reaction is protected from contamination. Experimentally though, the presence of small amounts of ammonia and simple amines (which should be permissible in Szostak’s scheme) react with methanal to bring the formose reaction to a grinding halt.

Reference:

Chyba, C. & Sagan,C., Endogenous Production, Exogenous delivery and Impact Shock Synthesis of Organic Molecules: An Inventory for the Origins of Life, Nature 355(1992): 125-32.

The concentrations of ribose would have been far too low to sanction any RNA world envisaged by Dr. Szostak. Compounding this is the added problem that ribose and other simple sugars are subject to oxidation under alkaline and acidic conditions, and since Szostak presents both hot and cold scenarios on the primitive Earth, it is noteworthy that ribose has a half life of only 73 minutes at 100C (near hydrothermal vents) and just 44 years at 0C.

Reference:

Oro, J., Early Chemical Changes in Origin of Life, from Early Life on Earth, Nobel Symposium No. 84, Bengtson, S. (ed.), pp 49-50, Columbia University Press (1994).

But there are more serious reasons why Szostak’s scheme of events could ever have happened on the primitive Earth. This is encapsulated in the so-called Oxygen-Ultraviolet Paradox.

Szostak envisages prebiotic synthesis in warm aqueous environments, but on the primordial Earth, some 3-4 Gyr ago, the presence of much higher levels of radionuclides such as uranium, thorium and potassium-40 would have presented another proverbial spanner in the works. These would have been more or less evenly distributed over the primitive Earth and when the radiation they emit passes though water, it causes its breakdown into molecular oxygen, hydrogen peroxide and other reactive oxygen species. Oxygen and the associated reactive oxygen species easily and quickly destroy organic molecules; not just ribose and other sugars, but the other biomolecules mentioned by Dr. Szostak too, including fatty acids and purine & pyrimidine bases required for the production of micelles(see Part II) and nucleotides, respectively .

The other part of the paradox pertains to the produce of stratospheric ozone, which requires ultraviolet light. The ozone layer was not present during the epoch in which Szostak’s scheme of events would have occurred. The intense UV irradiance on the primitive Earth would have sundered any exposed prebiotics, further compounding the problem.

References:

Draganic, I.G., Oxygen and Oxidizing Free Radicals in the Hydrosphere of the Earth, Book of Abstracts, ISSOL , 34 (1999) .

Draganic, I, Negron-Mendoza & Vujosevis, S.I, Reduction Chemistry of Water in Chemical Evolution Exploration, Book of Abstracts ISSOL, 139 (2002).

Dr. Szostak appears to be completely unaware of Draganic’s work (though citing Hazen and Deamer’s hydrothermal synthesis work @ 31 minutes) and indeed, in and of itself, would preclude any further discussions of his scheme of events. But we shall nonetheless persevere with this analysis.

This work will be continued in a new post (Part II) here.